Note: This page has been annotated with critical, historical, and cultural notes using the web annotation tool Hypothesis. You may view these annotations in the sidebar on the right-hand side of this page. Use the arrow icon to minimize the sidebar. A text-to-speech compatible transcript of the annotations for this page is available here.

The War of the Worlds in Pearson’s Magazine

Installment 4 of 9 (July 1897)

Pages from Pearson’s Magazine courtesy of HathiTrust, digitized by Google from originals at Indiana University.

[text marker: start page 108]

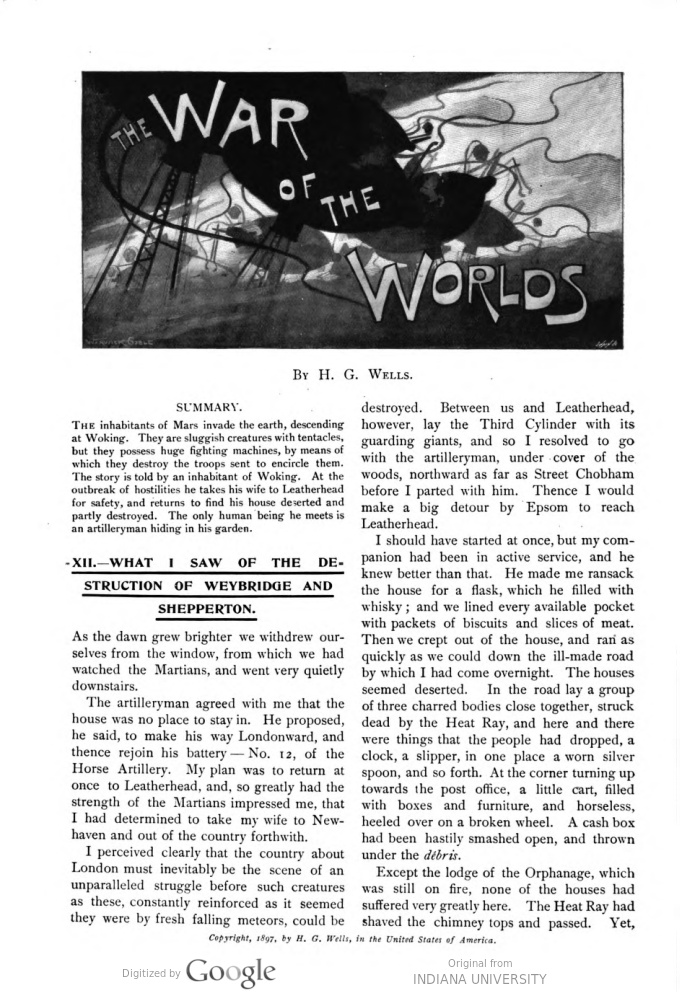

THE WAR OF THE WORLDS

BY H. G. WELLS

SUMMARY.

The inhabitants of Mars invade the earth, descending at Woking. They are sluggish creatures with tentacles, but they possess huge fighting machines, by means of which they destroy the troops sent to encircle them. The story is told by an inhabitant of Woking. At the outbreak of hostilities he takes his wife to Leatherhead for safety, and returns to find his house deserted and partly destroyed. The only human being he meets is an artilleryman hiding in his garden.

XII.―WHAT I SAW OF THE DESTRUCTION OF WEYBRIDGE AND SHEPPERTON.

As the dawn grew brighter we withdrew ourselves from the window, from which we had watched the Martians, and went very quietly downstairs.

The artilleryman agreed with me that the house was no place to stay in. He proposed, he said, to make his way Londonward, and thence rejoin his battery—No. 12, of the Horse Artillery. My plan was to return at once to Leatherhead, and, so greatly had the strength of the Martians impressed me, that I had determined to take my wife to Newhaven and out of the country forthwith.

I perceived clearly that the country about London must inevitably be the scene of an unparalleled struggle before such creatures as these, constantly reinforced as it seemed they were by fresh falling meteors, could be destroyed. Between us and Leatherhead, however, lay the Third Cylinder with its guarding giants, and so I resolved to go with the artilleryman, under cover of the woods, northward as far as Street Cobham before I parted with him. Thence I would make a big detour by Epsom to reach Leatherhead.

I should have started at once, but my companion had been in active service, and he knew better than that. He made me ransack the house for a flask, which he filled with whisky; and we lined every available pocket with packets of biscuits and slices of meat. Then we crept out of the house, and ran as quickly as we could down the ill-made road by which I had come overnight. The houses seemed deserted. In the road lay a group of three charred bodies close together, struck dead by the Heat Ray, and here and there were things that people had dropped, a clock, a slipper, in one place a worn silver spoon, and so forth. At the corner turning up towards the post office, a little cart, filled with boxes and furniture, and horseless, heeled over on a broken wheel. A cash box had been hastily smashed open, and thrown under the débris.

Except the lodge of the Orphanage, which was still on fire, none of the houses had suffered very greatly here. The Heat Ray had shaved the chimney tops and passed. Yet, [text marker: end page 108]

[text marker: start page 109] save ourselves, there did not seem to be a living soul on Maybury Hill. The majority of the inhabitants had escaped, I suppose, by way of the Old Woking road—the road I had taken when I drove to Leatherhead; or they had hidden.

We went down the lane by the body of the man in black, sodden now from the overnight hail, and broke into the woods at the foot of the hill. We pushed through these towards the railway, without meeting a soul. The woods across the line were but the scarred and blackened ruins of woods; for the most part the trees had fallen, but a certain proportion still stood, dismal grey stems with dark brown foliage instead of green.

On our side, the fire had done no more than scorch the nearer trees; it had failed to secure its footing. In one place, the woodmen had been at work on Saturday; trees, felled and freshly trimmed, lay in a clearing, with heaps of sawdust, by the sawing machine and its engine. Hard by was a temporary hut, deserted. There was not a breath of wind this morning, and everything was strangely still. Even the birds were hushed, and as we hurried along, I and the artilleryman talked in whispers, and looked now and again over our shoulders. Once or twice we stopped to listen.

After a time, we drew near the road, and as we did so, we heard the clatter of hoofs, and saw through the tree stems, three cavalry soldiers riding slowly towards Woking. We hailed them, and they halted while we hurried towards them. It was a lieutenant and a couple of privates of the Eighth Hussars, with a stand like a theodolite, which the artilleryman told me was a heliograph. “You are the first men I’ve seen coming this way this morning,” said the lieutenant. “What’s brewing?” His voice and face were eager. The men behind him stared curiously. The artilleryman jumped down the bank into the road and saluted. “Gun destroyed last night, Sir. Have been hiding. Trying to rejoin battery, Sir. You’ll come in sight of the Martians I expect about half a mile along this road.”

“What the dickens are they like?” asked the lieutenant.

“Giants in armour, Sir. Hundred feet high. Three legs and a body like ’luminium, with a mighty great head in a hood, Sir.”

“Get out!” said the lieutenant. “What confounded nonsense!”

“You’ll see, Sir. They carry a kind of box, Sir, that shoots fire and strikes you dead.”

“What d’ye mean—a gun?”

“No, Sir,” and the artilleryman began a vivid account of the Heat Ray. Halfway through the lieutenant interrupted him and looked up at me. I was still standing on the bank by the side of the road. “Did you see it?” said the lieutenant.

“It’s perfectly true,” I said.

“Well,” said the lieutenant, “I suppose it’s my business to see it too. Look here,”—to the artilleryman, “we’re detailed here clearing people out of their houses. You’d better go along and report yourself to Brigadier-General Marvin, and tell him all you know. He’s at Weybridge. Know the way?”

“I do,” I said; and he turned his horse southward again. “Half a mile, you say?” said he. “At most,” I answered, and pointed over the tree tops southward. He thanked me and rode on, and we saw them no more.

Farther along we came upon a group of three women and two children in the road, busy clearing out a labourer’s cottage. They had got hold of a kind of hand-truck, and were piling it up with unclean-looking bundles and shabby furniture. They were all too assiduously engaged to talk to us as we passed.

By Byfleet station we emerged from the pine trees, and found the country calm and peaceful under the morning sunlight. We were far beyond the range of the Heat Ray there, and had it not been for the silent desertion of some of the houses, the stirring movement of packing in others, and the knot of soldiers standing on the bridge over the railway and staring down the line towards Woking, the day would have seemed very like any other Sunday.

Several farm waggons and carts were moving creakily along the road to Addlestone, and suddenly through the gate of a field we saw, across a stretch of flat [text marker: end page 109]

[text marker: start page 110] meadow, six twelve-pounders, standing neatly at equal distances and pointing towards Woking. The gunners stood by the guns waiting, and the ammunition waggons were at a business-like distance. The men stood almost as if under inspection.

“That’s good!” said I. “They will get one fair shot at any rate.” The artilleryman hesitated at the gate. “I shall go on,” he said. Farther on towards Weybridge, just over the bridge, there were a number of men in white fatigue jackets throwing up a long rampart, and more guns behind. “It’s bows and arrows against the lightning, anyhow,” said the artilleryman. “They ’aven’t seen that fire beam yet.” The officers who were not actively engaged stood and stared over the tree-tops south-westward, and the men digging would stop every now and again to stare in the same direction.

Byfleet was in a tumult, people packing, and a score of hussars perhaps hunting them about, some of them dismounted, some on horseback. Three or four black Government waggons, with crosses in white circles, and an old omnibus, among other vehicles, were being loaded in the village street. There were scores of people, most of them sufficiently Sabbatical to have assumed their best clothes. The soldiers were having the greatest difficulty in making them realise the gravity of their position. We saw one shrivelled old fellow with a huge box and a score or more of flower-pots containing orchids, angrily expostulating with the corporal who would leave them behind. I stopped, and gripped his arm. “Do you know what’s over there?” I said, pointing at the pine-tops that hid the Martians.

“Eh?” said he, turning. “I was explainin’ these is vallyble.”

“Death!” I shouted. “Death is coming! Death!” and, leaving him to digest that if he could, I hurried on after the artilleryman. At the corner I looked back. The soldier had left him, and he was still standing by his box with the pots of orchids on the lid of it and staring vaguely over the trees.

No one in Weybridge could tell us where the headquarters were established, the whole place was in such confusion as I had never seen in any town before. Carts, carriages everywhere, the most astonishing miscellany of conveyances and horseflesh. The respectable inhabitants of the place, men in golf and boating costumes, wives prettily dressed, were packing, riverside loafers energetically helping, children excited, and, for the most part, highly delighted at this astonishing variation of their Sunday experiences. In the midst of it all the worthy vicar was very pluckily holding an early celebration, and his bell was jangling out above the excitement.

I and the artilleryman, seated on the step of the drinking fountain, made a very passable meal upon what we had brought with us. Patrols of soldiers—here no longer hussars but grenadiers in white—were warning people to move now or to take refuge in their cellars as soon as the firing began. We saw as we crossed the railway bridge that a growing crowd of people had assembled in and about the railway station, and the swarming platform was piled with boxes and packages. The ordinary traffic had been stopped, I believe, in order to allow of the passage of troops and guns to Chertsey, and I have heard since that a savage struggle occurred for places in the special trains that were put on at a later hour.

We remained at Weybridge until midday, and at that hour we found ourselves at the place near Shepperton Lock, where the Wey and Thames join. Part of the time we spent helping two old women to pack a little cart. The Wey has a treble mouth, and at this point boats are to be hired, and there was a ferry across the river. On the Shepperton side was an inn with a lawn, and beyond that the tower of Shepperton church—it has been replaced by a spire—rose above the trees.

Here we found an excited and noisy crowd of fugitives. As yet the flight had not grown to a panic, but there were already far more people than all the boats going to and fro could enable to cross. Quite respectable people came panting along under heavy burdens; one decent husband and wife were even carrying a small outhouse door between them, with some of their household goods piled thereon. One man told us he meant to try to get away from Shepperton station. [text marker: end page 110]

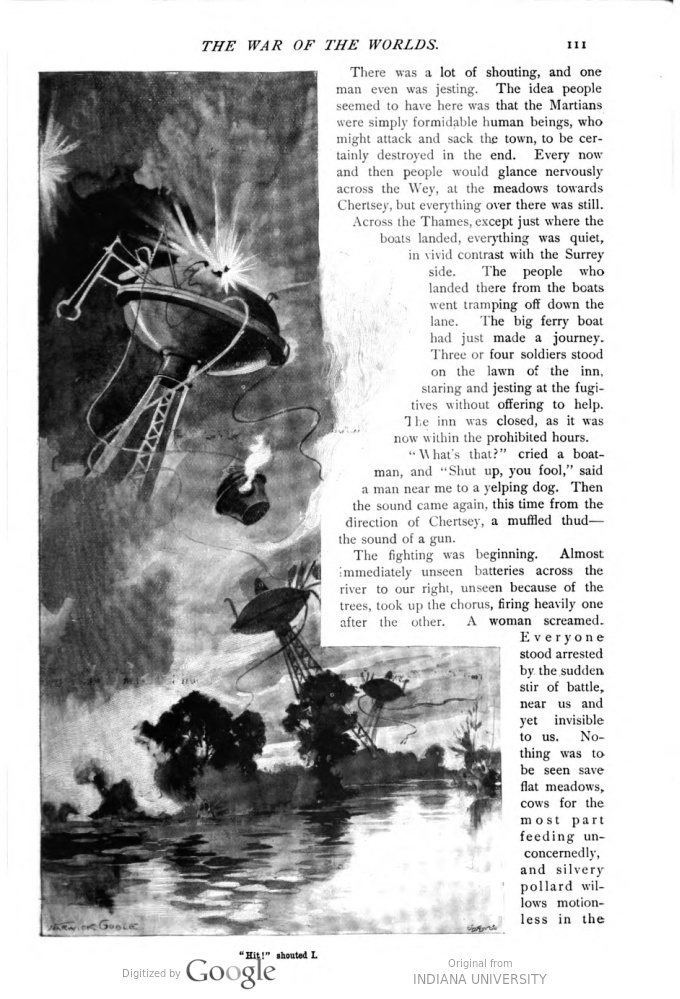

[text marker: start page 111] There was a lot of shouting, and one man was even jesting. The idea people seemed to have here was that the Martians were simply formidable human beings, who might attack and sack the town, to be certainly destroyed in the end. Every now and then people would glance nervously across the Wey, at the meadows towards Chertsey, but everything over there was still. Across the Thames, except just where the boats landed, everything was quiet, in vivid contrast with the Surrey side. The people who landed there from the boats went tramping off down the lane. The big ferry boat had just made a journey. Three or four soldiers stood on the lawn of the inn, staring and jesting at the fugitives without offering to help. The inn was closed, as it was now within the prohibited hours.

“What’s that?” cried a boatman, and “Shut up, you fool,” said a man near me to a yelping dog. Then the sound came again, this time from the direction of Chertsey, a muffled thud—the sound of a gun.

The fighting was beginning. Almost immediately unseen batteries across the river to our right, unseen because of the trees, took up the chorus, firing heavily one after the other. A woman screamed. Everyone stood arrested by the sudden stir of battle, near us and yet invisible to us. Nothing was to be seen save flat meadows, cows for the most part feeding unconcernedly, and silvery pollard willows motionless in the [text marker: end page 111]

[text marker: start page 112] warm sunlight. “The sojers’ll stop ’em,” said a woman beside me doubtfully. A haziness rose over the tree tops.

Then suddenly we saw a rush of smoke far away up the river, a puff of smoke that jerked up into the air, and hung, and forthwith the ground heaved under foot and a heavy explosion shook the air, smashing two or three windows in the houses near, and leaving us astonished.

“Here they are!” shouted a man in a blue jersey. “Yonder. D’yer see them? Yonder.”

Quickly, one after the other, one, two, three, four of the armed Martians appeared, far away over the little trees, across the flat meadows that stretch towards Chertsey, and striding hurriedly towards the river. Little cowled figures they seemed at first, going with a rolling motion, and as fast as flying birds.

Then, advancing obliquely towards us, came a fifth. Their armoured bodies glittered in the sun, as they swept swiftly forward upon the guns, growing rapidly larger as they drew nearer. One on the extreme left, the remotest that is, flourished a huge box high in the air, and the ghostly terrible Heat Ray I had already seen on Friday night smote towards Chertsey, and struck the town.

At sight of these strange, swift, and terrible creatures, the crowd along by the water’s edge seemed to me to be for a moment horrorstruck. There was no screaming or shouting but a silence.

Then a hoarse murmur and a movement of feet. A splashing from the water. A man, too frightened to drop the portmanteau he carried on his shoulder, swung round and sent me staggering with a blow from the corner of his burden. A woman thrust at me with her hand, and rushed past me. I turned too, with the rush of the people all ab out me. But I was not too terrified for thought. The terrible Heat Ray was in my mind. To get under water! That was it! “Get under water,” I shouted. I faced about again, and rushed towards the approaching Martian, rushed right down the gravelly beach, and headlong into the water. Others did the same. A boatload of people, putting back, came leaping out as I rushed past. The stones under my feet were muddy and slippery, and the river was so low that I ran perhaps twenty feet scarcely waist-deep. Then, as the Martian towered overhead scarcely a couple of hundred yards away, I flung myself forward under the surface. The splashes of the people in the boats leaping into the river sounded like thunderclaps in my ears.

In my convulsive excitement I took no heed of the artilleryman behind me, and to this day I do not know what became of him. I never set eyes on him again. People were landing hastily on both sides of the river.

But the Martian machine took no more notice for the moment of the people running this way and that, than a man would of the confusion of ants in a nest against which his foot has kicked. When, half suffocated, I raised my head above water―there were dripping faces all about me―the Martian’s hood pointed at the batteries that were still firing across the river, and as it advanced it swung loose what must have been the generator of the Heat Ray.

In another moment it was on the bank, and in a stride wading halfway across. The knees of its foremost legs bent at the further bank, and in another moment it had raised itself to its full height again, close to the village of Shepperton. Forthwith the six guns which, unknown to all of us on the right bank, had been hidden behind the outskirts of that village, fired simultaneously. The sudden concussions, the last close upon the first, made my heart jump. The monster was already raising the case generating the Heat Ray, as the shell burst six yards above the hood.

I gave a cry of astonishment. I saw and thought nothing of the other four Martian monsters; my attention was riveted upon the nearer incident. Simultaneously two other shells burst in the air near the body as the hood twisted round in time to receive, but not in time to dodge, the fourth shell.

The shell burst clean in the face of the thing. The hood bulged, flashed, was whirled off in a dozen tattered fragments of red flesh and glittering metal. “Hit!” shouted I, with something between a scream and a cheer. I heard answering shouts from the people in the water about me. I could have [text marker: end page 112]

[text marker: start page 113] leaped out of the water with that momentary exultation.

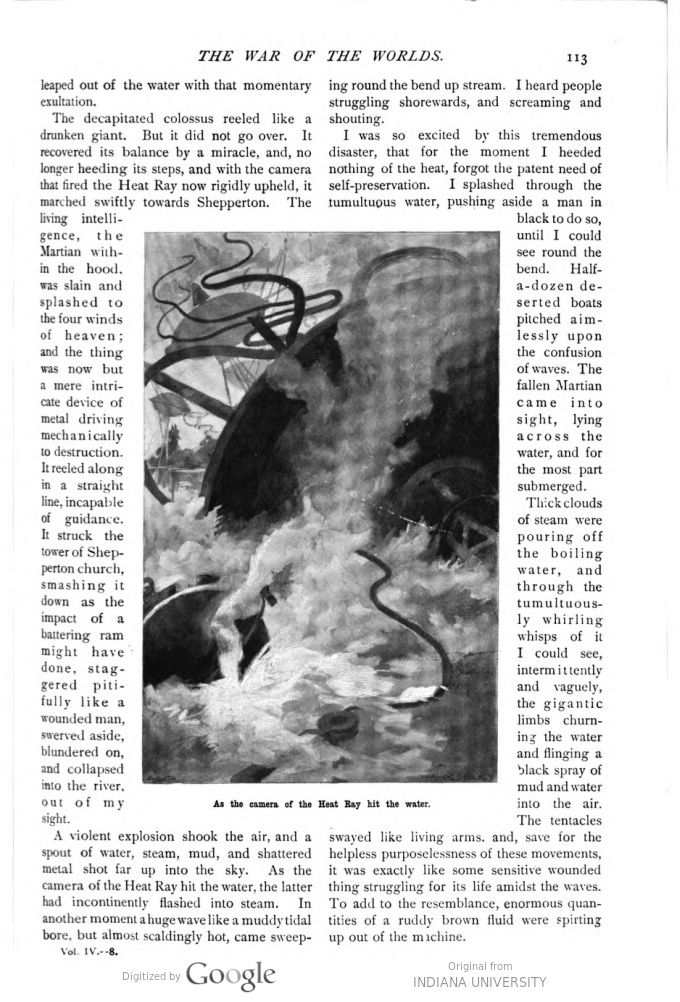

The decapitated colossus reeled like a drunken giant. But it did not go over. It recovered its balance by a miracle, and, no longer heeding its steps, and with the camera that fired the Heat Ray now rigidly upheld, it marched swiftly towards Shepperton. The living intelligence, the Martian within the hood, was slain and splashed to the four winds of heaven; and the thing was now but a mere intricate device of metal driving mechanically to destruction. It reeled along in a straight line, incapable of guidance. It struck the tower of Shepperton church, smashing it down as the impact of a battering ram might have done, staggered pitifully like a wounded man, swerved aside, blundered on, and collapsed into the river, out of my sight.

A violent explosion shook the air, and a spout of water, steam, mud, and shattered metal shot far up into the sky. As the camera of the Heat Ray hit the water, the latter had incontinently flashed into steam. In another moment a huge wave like a muddy tidal bore, but almost scaldingly hot, came sweeping round the bend up stream. I heard people struggling shorewards, and screaming and shouting.

I was so excited by this tremendous disaster, that for the moment I heeded nothing of the heat, forgot the patent need of self-preservation. I splashed through the tumultuous water, pushing aside a man in black to do so, until I could see round the bend. Half-a-dozen deserted boats pitched aimlessly upon the confusion of the waves. The fallen Martian came into sight, lying across the water, and for the most part submerged.

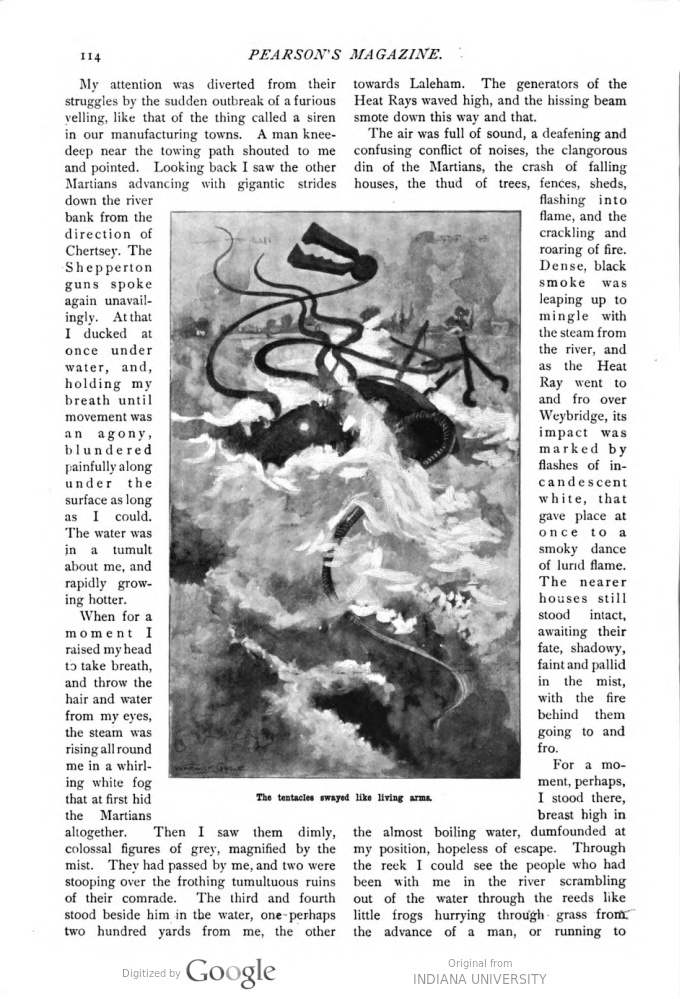

Thick clouds of steam were pouring off the boiling water, and through the tumultuously whirling wisps of it I could see, intermittently and vaguely, the gigantic limbs churning the water and flinging a black spray of mud and water into the air. The tentacles swayed like living arms, and, save for the helpless purposelessness of these movements, it was exactly like some sensitive wounded thing struggling for its life amidst the waves. To add to the resemblance, enormous quantities of a ruddy brown fluid were spirting up out of the machine. [text marker: end page 113]

[text marker: start page 114] My attention was diverted from their struggles by the sudden outbreak of a furious yelling, like that of the thing called a siren in our manufacturing towns. A man knee-deep near the towing path shouted to me and pointed. Looking back I saw the other Martians advancing with gigantic strides down the river bank from the direction of Chertsey. The Shepperton guns spoke again unavailingly. At that I ducked at once under water, and, holding my breath until movement was an agony, blundered painfully along under the surface as long as I could. The water was in a tumult about me, and rapidly growing hotter.

When for a moment I raised my head to take breath, and throw the hair and water from my eyes, the steam was rising all around me in a whirling white fog that at first hid the Martians altogether. Then I saw them dimly, colossal figures of grey, magnified by the mist. They had passed by me, and two were stooping over the frothing tumultuous ruins of their comrade. The third and fourth stood beside him in the water, one perhaps two hundred yards from me, the other towards Laleham. The generators of the Heat Rays waved high, and the hissing beam smote down this way and that.

The air was full of sound, a deafening and confusing conflict of noises, the clangorous din of the Martians, the crash of falling houses, the thud of trees, fences, sheds, flashing into flame, and the crackling and roaring of fire. Dense, black smoke was leaping up to mingle with the steam from the river, and as the Heat Ray went to and fro over Weybridge, its impact was marked by flashes of incandescent white, that gave place at once to a smoky dance of lurid flame. The nearer houses still stood intact, awaiting their fate, shadowy, faint and pallid in the mist, with the fire behind them going to and fro.

For a moment, perhaps, I stood there, breast high in the almost boiling water, dumbfounded at my position, hopeless of escape. Through the reek I could see the people who had been with me in the river scrambling out of the water through the reeds like little frogs hurrying through grass from the advance of a man, or running to [text marker: end page 114]

[text marker: start page 115] and fro in utter dismay on the towing path.

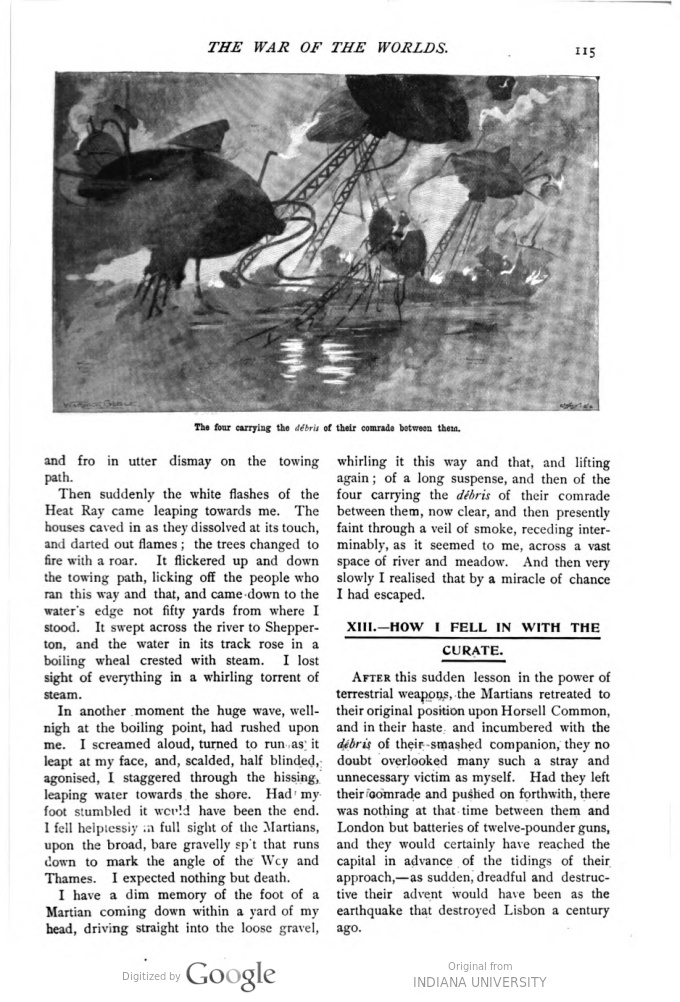

Then suddenly the white flashes of the Heat Ray came leaping towards me. The houses caved in as they dissolved at its touch, and darted out flames; the trees changed to fire with a roar. It flickered up and down the towing path, licking off the people who ran this way and that, and came down to the water’s edge not fifty yards from where I stood. It swept across the river to Shepperton, and the water in its track rose in a boiling wheal crested with steam. I lost sight of everything in a whirling torrent of steam.

In another moment the huge wave, well-nigh at the boiling-point, had rushed upon me. I screamed aloud, turned to run as it leapt at my face, and, scalded, half blinded, agonised, I staggered through the hissing, leaping water towards the shore. Had my foot stumbled it would have been the end. I fell helplessly in full sight of the Martians, upon the broad, bare gravelly spit that runs down to mark the angle of the Wey and Thames. I expected nothing but death.

I have a dim memory of the foot of a Martian coming down within a yard of my head, driving straight into the loose gravel, whirling it this way and that, and lifting again; of a long suspense, and then of the four carrying the débris of their comrade between them, now clear, and then presently faint through a veil of smoke, receding interminably, as it seemed to me, across a vast space of river and meadow. And then very slowly I realised that by a miracle of chance I had escaped.

XIII.―HOW I FELL IN WITH THE CURATE.

After this sudden lesson in the power of terrestrial weapons, the Martians retreated to their original position upon Horsell Common, and in their haste and incumbered with the débris of their smashed companion, they no doubt overlooked many such a stray and unnecessary victim as myself. Had they left their comrade and pushed on forthwith, there was nothing at that time between them and London but batteries of twelve-pounder guns, and they would certainly have reached the capital in advance of the tidings of their approach,―as sudden, dreadful and destructive their advent would have been as the earthquake that destroyed Lisbon a century ago. [text marker: end page 115]

[text marker: start page 116] But they were in no hurry. Cylinder followed cylinder in its interplanetary flight; every twenty-four hours brought them reinforcement. And meanwhile the military and naval authorities now fully alive to the tremendous power of their antagonists, worked with furious energy. Every minute a fresh gun came into position, until, before twilight, every copse, every row of suburban villas on the hilly slopes about Kingston and Richmond, masked an expectant black muzzle. And through the charred and desolated area—perhaps twenty square miles altogether—that encircled the Martian encampment on Horsell Common, through charred and ruined villages among the green trees, through the blackened and smoking arcades that had been but a day ago pine spinneys, crawled the devoted scouts with the heliographs that were presently to warn the gunners of the Martian approach. But the Martians now understood our command of artillery and the danger of human proximity, and not a man ventured within a mile of either cylinder save at the price of his life.

It would seem that these giants spent the earlier part of the afternoon in going to and fro, transferring everything from the second and third cylinders—the second in Addlestone Golf Links and the third at Pyrford—to their original pit on Horsell Common. Over that, one stood sentinel above the blackened heather and ruined buildings that stretched far and wide, while the rest abandoned their vast fighting machines and descended into the pit. They were hard at work there far into the night, and the towering pillar of [text marker: end page 116]

[text marker: start page 117] dense green smoke that rose thencefrom, could be seen from the hills about Merrow, and even, it is said, from Banstead and Epsom Downs.

And while the Martians behind me were thus preparing for their next sally, and in front of me Humanity gathered for the battle, I made my way with infinite pains and labour from the fire and smoke of burning Weybridge towards London. When I realised that the Martians had passed I struggled to my feet, giddy and smarting from the scalding I received, and for a space I stood sick and helpless between the drifting steam and the suffocating, burning, and smouldering behind.

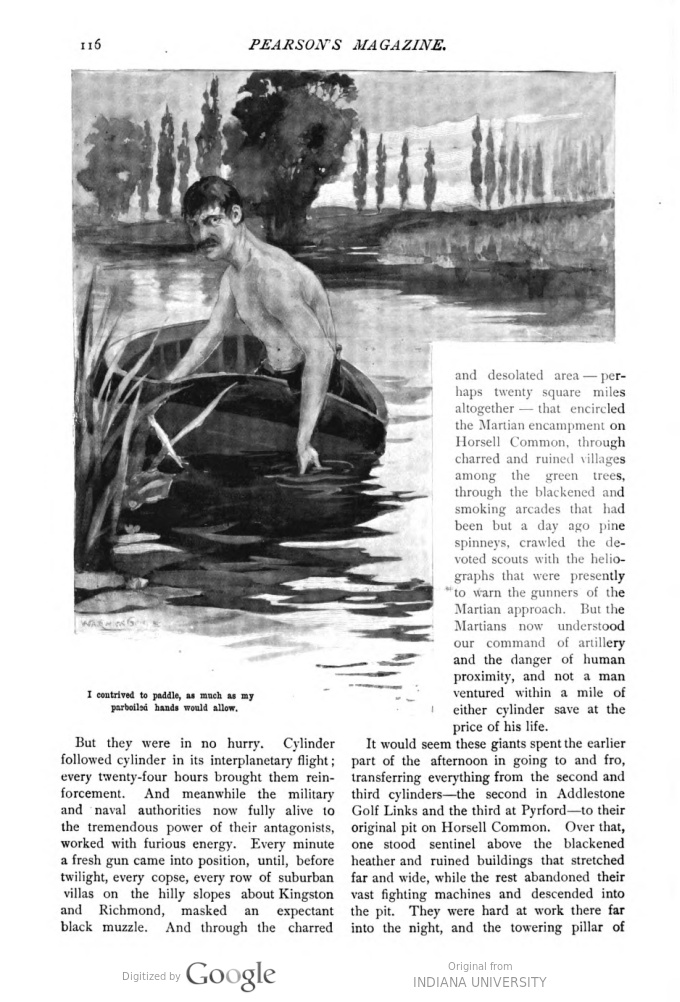

Presently, through a gap in the thinning steam, I saw an abandoned boat, very small and remote, drifting down stream, and throwing off the most of my sodden and blackened clothes, I went after it, gained it, and so escaped out of that destruction. There were no oars in the boat, but I contrived to paddle, as much as my parboiled hands would allow, down the river towards Halliford and Walton, going very tediously, and continually looking behind me, as you may well understand.

The hot water from the Martian’s overthrow drifted down stream with me, so that for the best part of a mile I could see little of either bank. Once, however, I made out a string of black figures hurrying across the meadows from the direction of Weybridge. Halliford, it seemed, was quite deserted, and several of the houses facing the river were afire. It was strange to see the place quite tranquil, quite desolate, under the hot blue sky, with the smoke and little threads of flame going straight up into the heat of the afternoon. Never before had I seen houses burning without the accompaniment of an inconvenient crowd. A little further on the dry reeds up the bank were smoking and glowing, and a line of fire inland was marching steadily across a late field of hay.

For a long time I drifted, so painful and weary was I after the violence I had been through, and so intense the heat upon the water. Then my fears got the better of me again, and I resumed my paddling. The sun scorched my bare back. At last, as the bridge at Walton was coming into sight round the bend, my fever and faintness overcame my fears, and I landed on the Middlesex bank, and lay down, deadly sick, amidst the long grass. I suppose the time was then about four or five o’clock. I got up presently, walked perhaps half a mile without meeting a soul, and then lay down again in the shadow of a hedge. I seem to remember talking wanderingly to myself during that last spurt. I was also very thirsty, and bitterly regretful I had drunk no more water.

I do not clearly remember the arrival of the curate, so that I probably dozed. I became aware of him as a seated figure in soot-smudged shirt sleeves, and with his upturned clean-shaven face, staring at a faint flickering that danced over the sky. The sky was what is called a mackerel sky, rows and rows of faint down-plumes of cloud, just tinted with the midsummer sunset.

I sat up, and, at the rustle of my motion, he looked at me quickly. “Have you any water?” I asked abruptly.

He shook his head. “You have been asking for water for the last hour,” he said unsympathetically.

For a moment we were silent, taking stock of one another. I daresay he found me a strange enough figure, naked save for my water-soaked trousers and socks, scalded, and my face and shoulders blackened from the smoke. His face was a dead white, his eyes were pale grey, and blankly staring. He spoke abruptly, looking vacantly away from me.

“What does it mean?” he said. “What do these things mean?”

I stared at him and made him no answer.

He extended a thin, white hand and spoke in almost a complaining tone. “Why are these things permitted? What sins have we done? The morning service was over, I was walking through the roads to clear my brain for the afternoon’s catechism, and then comes fire, earthquake, Death! As if it were Sodom and Gomorrah! All our work undone, all the work and the lives of hundreds of men. . . . . . Does God care? What are these Martians?” [text marker: end page 117]

[text marker: start page 118] “What are we?” I answered, clearing my throat.

He gripped his knees and turned to look at me again. For half a minute, perhaps, he stared silently. “Aye!” he said; “what are we?” He relapsed into silence, with his chin now sunken almost to his knees.

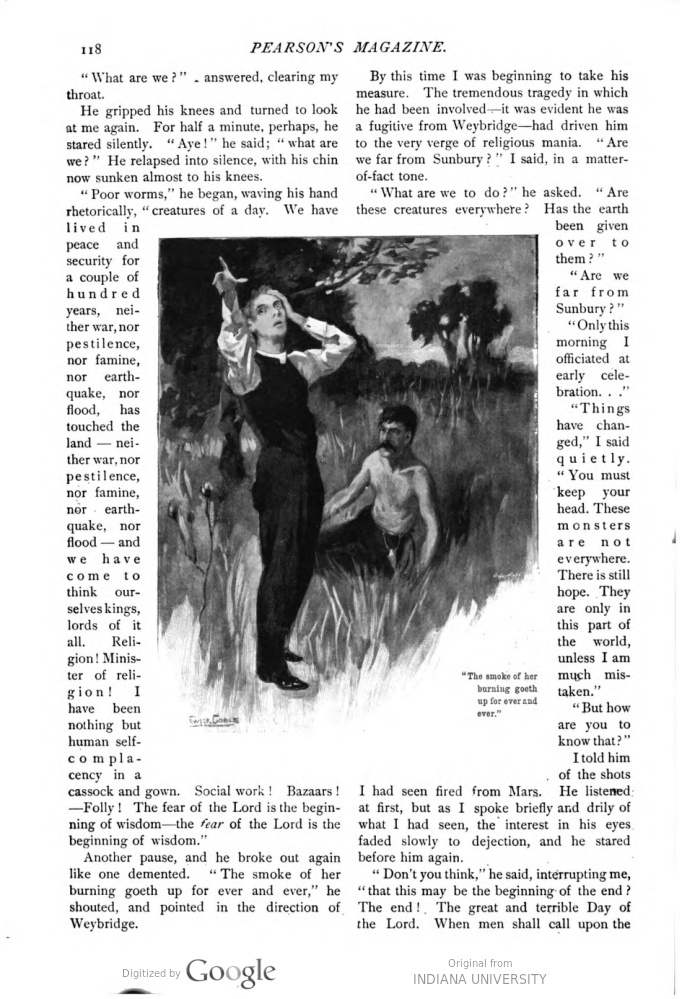

“Poor worms,” he began, waving his hand rhetorically, “creatures of a day. We have lived in peace and security for a couple of hundred years, neither war, nor pestilence, nor famine, nor earthquake, nor flood, has touched the land―neither war, nor pestilence, nor famine, nor earthquake, nor flood―and we have come to think ourselves kings, lords of it all. Religion! Minister of religion! I have been nothing but human self-complacency in a cassock and gown. Social work! Bazaars!―Folly! The fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom―the fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom.”

Another pause, and he broke out again like one demented. “The smoke of her burning goeth up for ever and ever,” he shouted, and pointed in the direction of Weybridge.

By this time I was beginning to take his measure. The tremendous tragedy in which he had been involved—it was evident he was a fugitive from Weybridge—had driven him to the very verge of religious mania. “Are we far from Sunbury?” I said, in a matter-of-fact tone.

“What are we to do?” he asked. “Are these creatures everywhere? Has the earth been given over to them?”

“Are we far from Sunbury?”

“Only this morning I officiated at early celebration. . .”

“Things have changed,” I said quietly. “You must keep your head. These monsters are not everywhere. There is still hope. They are only in this part of the world, unless I am much mistaken.”

“But how are you to know that?”

I told him of the shots I had seen fired from Mars. He listened at first, but as I spoke briefly and drily of what I had seen, the interest in his eyes faded slowly to dejection, and he stared before him again.

“Don’t you think,” he said, interrupting me, “that this may be the beginning of the end? The end! The great and terrible Day of the Lord. When men shall call upon the [text marker: end page 118]

[text marker: start page 119] mountains and the rocks to fall upon them and hide them—hide them from the face of Him that sitteth upon the throne?”

I stared blankly by way of answer, then rose painfully to my feet and, standing over him, laid my hand on his shoulder. “Drop that Book of Revelations,” said I, “and be a man. You are scared out of your wits. After all, this is the way of Nature. What good is religion if it collapses at calamity? Think of what earthquakes and floods, wars and volcanoes, have done before to men. Did you think God had exempted Weybridge on your account? One would think, to hear you, that He had made you a special promise―and broken it. . . . . . God is not an insurance agent, man.”

“But how can we escape?” he asked more quietly. “They are invulnerable, they are pitiless.”

“Neither the one nor perhaps the other,” I answered. “And the mightier they are the more sane and wary should we be. One of them was killed yonder not three hours ago.

“I saw it happen,” I said, and told him. “We have chanced to come in for the thick of it, and that is all.”

“What is that flicker in the sky?” he asked abruptly.

I told him it was simply the heliograph signalling. A cockchafer came droning over the hedge and past us. High in the west the crescent moon hung faint and pale, above the smoke of Weybridge and Shepperton and the hot splendour of the sunset.

“We are in the midst of it,” I said, “quiet as it is. That flicker in the sky tells of the gathering storm. Yonder, I take it, are the Martians, and Londonward where those hills rise about Richmond and Kingston, and the trees give cover, earthworks are being thrown up and guns are being laid. Presently the Martians will be coming this way again. . .”

And even as I spoke, he sprang to his feet and stopped me by a gesture. “Listen!” he said. And from far away from beyond the low hills across the water, came the dull resonance of guns and a remote, weird crying.

“We had better follow this path,” I said, “northward.”

(To be continued next month.)

[text marker: end page 119, end installment 4]

previous installment | next installment

The following is the text of a poem that appears in the bottom half of page 119. It was common practice for Victorian periodicals to fill parts of pages with poetry or other short pieces that are unrelated to the other text on a given page.

THE PHANTOM KISS.

One night in my room, still and beamless

With will and with thought in eclipse,

I rested in sleep that was dreamless;

When softly there fell on my lips

A touch, as if lips that were pressing

Mine own with the message of bliss—

A sudden, soft, fleeting caressing,

A breath like a maiden’s first kiss.

I woke—and the scoffer may doubt me—

I peered in surprise through the gloom;

But nothing and none were about me,

And I was alone in my room.

Perhaps ’twas the wind that caressed me

And touched me with dew-laden breath;

Or, maybe, close-sweeping, there passed me

The low-winging Angel of Death.

Some sceptic may choose to disdain it,

Or one feign to read it aright;

Or wisdom may seek to explain it—

This mystical kiss in the night.

But rather let fancy thus clear it:

That, thinking of me here alone,

The miles were made naught, and, in spirit,

Thy lips, love, were laid on mine own.

PAUL LAURENCE DUNBAR.