Note: This page has been annotated with critical, historical, and cultural notes using the web annotation tool Hypothesis. You may view these annotations in the sidebar on the right-hand side of this page. Use the arrow icon to minimize the sidebar. A text-to-speech compatible transcript of the annotations for this page is available here.

The War of the Worlds in Pearson’s Magazine

Installment 9 of 9 (December 1897)

Pages from Pearson’s Magazine courtesy of HathiTrust, digitized by Google from originals at Indiana University.

[text marker: start page 736]

THE WAR OF THE WORLDS

BY H. G. WELLS

XXI.―AFTER THE FIFTEEN DAYS (continued).

The further I penetrated into London, the profounder grew the silence. But it was not so much the stillness of death, it was the stillness of suspense, of expectation. Somehow I felt that this was not the end. I had a sense of things still impending. Suppose the Martians were, after all, at hand. At any time the destruction that already singed the north-western borders of the Metropolis, and had annihilated Ealing and Kilburn, might strike among these houses and leave them smoking ruins. It was a city condemned and derelict. . . . That, at any rate, would be completion.

In South Kensington the streets were clear of dead and of black powder. It was near South Kensington that I first heard the howling. It crept almost imperceptibly upon my senses. It was a sobbing alternation of two notes, “Ulla, ulla, ulla, ulla,” keeping on perpetually. When I passed streets that ran northward it grew in volume, and houses and buildings seemed to deaden and cut it off again. It came in a full tide down Exhibition Road. I stopped staring towards Kensington Gardens, wondering at this strange remote wailing. It was as if that mighty desert of houses had found a voice for its fear and solitude.

“Ulla, ulla, ulla, ulla,” wailed that superhuman note; great waves of sound sweeping down the broad, sunlit roadway, between the tall buildings on either side. I turned northward, marvelling, towards the iron gates of Hyde Park. I had half a mind to break into the Natural History Museum and find my way up to the summits of the towers, in order to see across the Park. But I decided to keep to the ground, where quick hiding was possible, and so went on up the Exhibition Road. All the large mansions on either side of the road were empty and still, and my footsteps echoed against the sides of the houses. At the top, near the park gate, I came upon a strange sight—a ’bus overturned, and the skeleton of a horse picked clean. I puzzled over this for a time, and then went on to the bridge over the Serpentine. The Voice grew stronger and stronger, though I could see nothing above the housetops on the north side of the park, save a haze of smoke to the north-west.

“Ulla, ulla, ulla, ulla,” cried the voice, coming, as it seemed to me, from somewhere beyond Baker Street. The desolating cry worked upon my mind. The mood that had sustained me passed. The wailing took possession of me. I found I was intensely weary, footsore, and now again hungry and thirsty.

It was already past noon. Why was I wandering alone in this city of the dead? Why was I alone when all London was lying in state, and in its black shroud? I was intolerably lonely. My mind ran on old friends that I had forgotten for years. I [text marker: end page 736]

[text marker: start page 737] thought of the poisons in the chemists’ shops, of the liquors the wine merchants stored, I recalled the two sodden creatures of despair who, so far as I knew, shared the city with myself . . . . We were the last of men.

I came into Oxford Street by the Marble Arch, and here again was black powder and several bodies, and an evil, ominous smell from the gratings of the cellars of some of the houses. I grew very thirsty after the heat of my long walk. With infinite trouble I managed to break into a public-house and get food and drink. I was weary after eating, and went into the parlour behind the bar and slept on a black horsehair sofa I found there.

I awoke to find that dismal howling still in my ears: “Ulla, ulla, ulla, ulla.” It was now dusk, and after I had routed out some biscuits and a cheese in the bar—there was cold beef there also in a safe, but it was too bad to eat—I wandered on through the silent residential squares to Baker Street—Portman Square is the only one I can name—and so came out at last upon Regent’s Park. And as I emerged from the top of Baker Street, I saw far away over the trees in the clearness of the sunset, the hood of the Martian giant from which this howling proceeded. I was not terrified. I came upon him as if it were a matter of course. I watched him for some time, but he did not move. He appeared to be standing and yelling, for no reason that I could discover.

I tried to formulate a plan of action. That perpetual sound of “Ulla, ulla, ulla, ulla,” confused my mind. Perhaps I was too tired to be very fearful. Certainly I was rather curious than afraid to know the reason of this monotonous crying. I turned back away from the park and struck into Park Road, intending to skirt the park, and went along under the shelter of the terraces and got a view of this stationary howling Martian from the direction of St. John’s Wood. A couple of hundred yards out of Baker Street I heard a yelping chorus, and saw, first, a dog with a piece of putrescent red meat in his jaws coming headlong towards me, and then a pack of starving mongrels in pursuit of him. He made a wide curve to avoid me, as though he feared I might prove a fresh competitor. As the yelping died away down the silent road, the wailing sound of “Ulla, ulla, ulla,” reasserted itself.

I came upon the wrecked Handling Machine halfway to St. John’s Wood station. At first I thought that a house had fallen across the road. It was only as I clambered among the ruins that I saw, with a start, this mechanical Samson lying, with its tentacles bent and smashed and twisted, among the ruins it had made. The forepart was shattered. It seemed as if it had driven blindly straight at the house and had been overwhelmed in its overthrow. It seemed to me then that this might have happened by a Handling Machine escaping from the guidance of its Martian. I could not clamber among the ruins to see it, and the twilight was now so far advanced that the blood with which its seat was smeared and the gnawed gristle of the Martian that the dogs had left, was invisible to me.

Wondering still more at all that I had seen, I pushed on towards Primrose Hill. Far away, through a gap in the trees, I saw a second Martian, motionless as the first, standing in the park towards the Zoological Gardens, and silent. A little beyond the ruins about the smashed Handling Machine I came upon the Red Weed again, and found the Regent’s Canal, a spongy mass of dark red vegetation.

Abruptly, as I crossed the bridge, the sound of “Ulla, ulla, ulla,” ceased. It was, as it were, cut off. The silence came like a thunderclap.

The dusky houses about me stood faint, and tall and dim, the trees towards the park were growing black. Night, the Mother of Fear and Mystery, was coming upon me. But while that voice sounded the solitude, the desolation had been endurable; by virtue of it London had still seemed alive, and the sense of life about me had upheld me. Then suddenly, a change, the passing of something—I knew not what—and then a stillness that could be felt. Nothing but this gaunt quiet of death!

London about me gazed at me spectrally. The windows in the white houses were like the eye-sockets of skulls. About me my imagination found a thousand noiseless enemies moving. Terror seized me, a horror [text marker: end page 737]

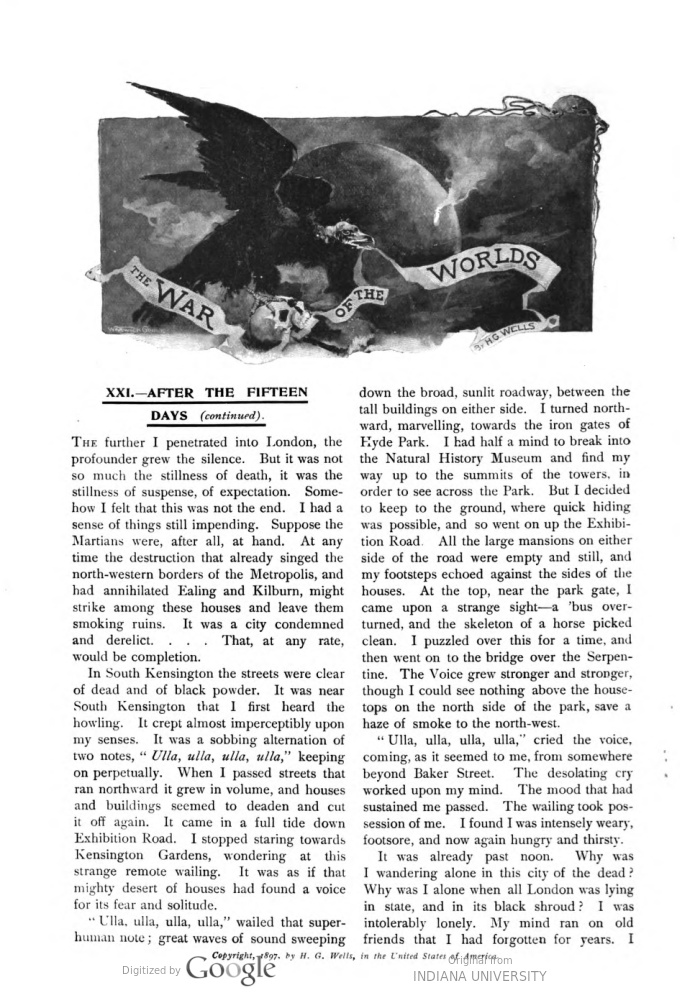

[text marker: start page 738] of my temerity. In front of me the road became pitchy black as though it was tarred, and I saw a contorted shape lying across the pathway. I could not bring myself to go on. I turned down St. John’s Wood Road, and ran headlong from this unendurable stillness towards Kilburn. I hid from the night and the silence, until long after midnight, in a cabmen’s shelter in the Harrow Road. But before the dawn my courage returned, and while the stars were still in the sky, I turned once more towards the Regent’s Park. I missed my way among the streets, and presently saw, down a long avenue, in the half light of early dawn, the curve of Primrose Hill. On the summit, towering up to the fading stars, was a third Martian, erect and motionless like the others.

A strange insanity seized upon me. I would die and end it. And I would save myself even the trouble of killing myself. I marched on recklessly towards this Titan, and then, as I drew nearer and the light grew, I saw that a multitude of black birds was circling and clustering about the hood. At that my heart gave a bound, and I began running along the road. I hurried through the red weed that choked St. Edmund’s Terrace (a torrent of water was rushing down from the waterworks towards the Albert Road) and emerged upon the grass before the rising of the sun. Great mounds had been heaped about the crest of the hill, making a huge redoubt of it, and from behind them rose a thin smoke against the sky. Against the skyline an eager dog ran and disappeared. The thought that had flashed into my mind, grew real, grew credible. I felt no fear, only a wild exultation, as I ran up the hill, towards the motionless monster. Out of the hood hung lank shreds of brown at which the hungry birds pecked and tore.

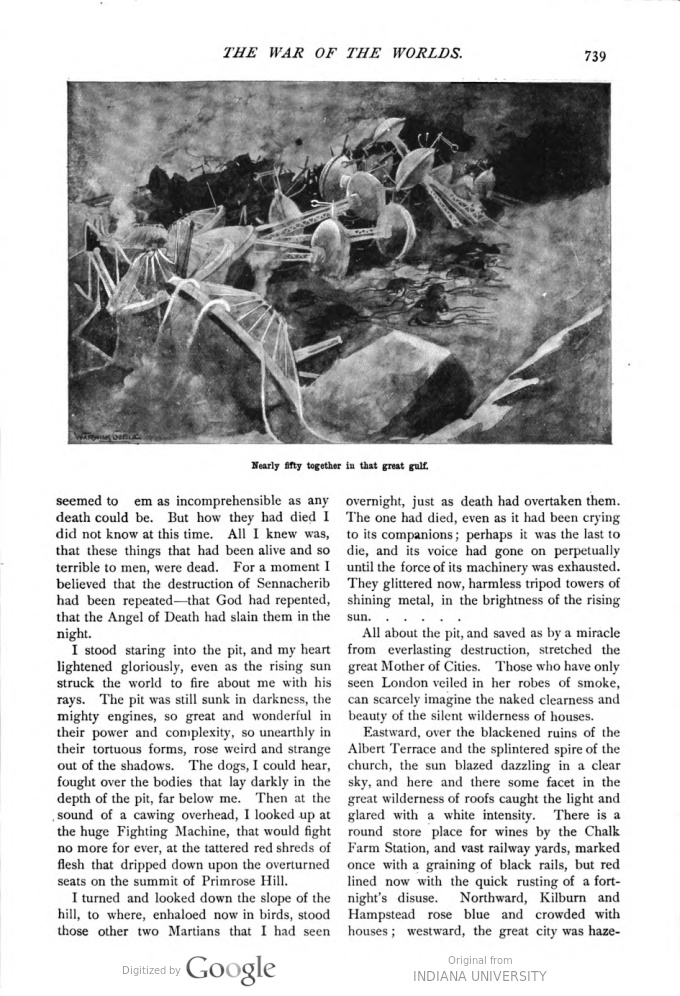

In another moment I had scrambled up the earthen rampart and stood upon its crest, and the interior of the redoubt was below me. A mighty space it was, with gigantic machines here and there within it, huge mounds of material, and rough hewn shelter places. And scattered about it, some in their overturned war machines, some in the now rigid Handling Machines, and a dozen of them, stark and silent and laid in a row, were the Martians—dead!—Slain by the putrefactive and disease bacteria, against which their systems were unprepared; slain, after all man’s devices had failed, by the humblest things that God has put upon this earth.

Here and there they were scattered, nearly fifty altogether in that great gulf they had made, overtaken by a death that must [text marker: end page 738]

[text marker: start page 739] have seemed to them as incomprehensible as any death could be. But how they had died I did not know at this time. All I knew was, that these things that had been alive and so terrible to men, were dead. For a moment I believed that the destruction of Sennacherib had been repeated—that God had repented, that the Angel of Death had slain them in the night.

I stood staring into the pit, and my heart lightened gloriously, even as the rising sun struck the world to fire about me with his rays. The pit was still in darkness, the mighty engines, so great and wonderful in their power and complexity, so unearthly in their tortuous forms, rose weird and strange out of the shadows. The dogs, I could hear, fought over the bodies that lay darkly in the depth of the pit, far below me. Then at the sound of a cawing overhead, I looked up at the huge Fighting Machine, that would fight no more for ever, at the tattered red shreds of flesh that dripped down upon the overturned seats on the summit of Primrose Hill.

I turned and looked down the slope of the hill, to where, enhaloed now in birds, stood those other two Martians that I had seen overnight, just as death had overtaken them. The one had died, even as it had been crying to its companions; perhaps it was the last to die, and its voice had gone on perpetually until the force of its machinery was exhausted. They glittered now, harmless tripod towers of shining metal, in the brightness of the rising sun. . . . . .

All about the pit, and saved as by a miracle from everlasting destruction, stretched the great Mother of Cities. Those who have only seen London veiled in her robes of smoke, can scarcely imagine the naked clearness and beauty of the silent wilderness of houses.

Eastward, over the blackened ruins of the Albert Terrace and the splintered spire of the church, the sun blazed dazzling in a clear sky, and here and there some facet in the great wilderness of roofs caught the light and glared with a white intensity. There is a round store place for wines by the Chalk Farm Station, and vast railway yards, marked once with a graining of black rails, but red lined now with the quick rusting of a fortnight’s disuse. Northward, Kilburn and Hampsted rose blue and crowded with houses; westward the great city was haze- [text marker: end page 739]

[text marker: start page 740] dimmed; and southward, beyond the Martians, the green waves of Regent’s Park, the Langham Hotel, the dome of the Albert Hall, the Imperial Institute, and the giant mansions of the Brompton Road came out clear and little in the sunrise with the jagged ruins of Westminster beyond. Far away the Surrey hills rose up, and the towers of the Crystal Palace glittered like two silver rods. The dome of St. Paul’s was dark against the sunrise, and injured, I saw for the first time, by a huge gaping cavity on its westward side.

And, as I looked at this wide expanse of houses, and factories, and churches, silent and abandoned, as I thought of the multitudinous hopes and efforts, the innumerable hosts of lives that had gone to build this human reef, and of the swift and ruthless destruction that had hung over it all, when I realised that the shadow had been rolled back, and that men might still live in its streets, and this dear vast dead city of mine be once more alive and powerful, I felt a wave of emotion, that was near akin to tears.

The torment was over. Even that day, the healing would begin. The survivors of the people scattered over the country, leaderless, lawless, foodless, like sheep without a shepherd, the thousands who had fled by sea would begin to return; the pulse of life, growing stronger and stronger, would beat again in the empty streets, and pour across the vacant squares. Whatever destruction was done, the hand of the destroyer was stayed. All the gaunt wrecks, the blackened skeletons of houses that stared so dismally at the sunlit grass of the hill, would presently be echoing under the hammers of the restorers, and ringing with the tintinnabulations of the trowels. At the thought, I extended my hands towards the sky, and began thanking God. In a year, thought I,—in a year. . . . and then, with overwhelming force, came the thought of myself, of my wife, and the old life, that I had to imagine done with for ever. [text marker: end page 740]

[text marker: start page 741]

XXII.―THE EPILOGUE.

But here the story that will interest the general reader, the story of the Martians, ends. The rest, the return, the Thanksgiving, has been written by a thousand pens. This is indeed no history, it is a mere clumsy narrative of my own personal adventures during this strange time, eked out by my brother’s experience where the gaps were too great. Such narratives we must have first in abundance, and afterwards the history may be written. In the fact that I was among the first to see the Martians at their arrival, and the second man—indeed, I had fancied myself first—to discover them dead, I have presumed to think my impressions might be of value. And by an odd coincidence, of the four Martians killed by Man, I saw the death of one and my brother the overthrow of two others. But to tell of the torrent of people that presently flowed back into London, chiefly from the north—for the Martians had never gone further than forty miles in that direction—of the riots and plundering, and murders, of the restoration of government, of the terrific explosion of the Heat Ray powder that wrecked the north of London, hundreds are better qualified than I.

Nor have I any qualification to speak of the distresses in the home counties, the famine, the violence, even it is said, the cannibalism, and disappearance of all law and order during the fortnight of the war, and afterwards the struggle with the pestilence. It speaks eloquently for the lesson that humanity had learned that no attack was made on our stricken Empire during the months of reconstruction.

I plundered a grocer’s shop in Camden Town for food, on the morning of my discovery, and afterwards tramped down to the docks with the idea of spreading the good news there. In Shoreditch I met people again, and told them what I had seen; and it was from the General Post Office, by a Jewess who had learned the trade of a telegraph operator, that the news was first flashed out of London, to Paris first, and then to certain English towns.

I remember that I laughed hysterically until I cried, when, after infinite trouble and muddling, we managed the telephone, and heard the French operator say, over and over again as though they were his only words: “Dead! Nom de Dieu! A Tousand Congratulation. You have kill dem? Vive l’Angleterre! Hooray!” Its kindly insipidity offered such an infinite contrast to the half dozen haggard yellow faced dirty and hungry people who crowded into the room. That night, I have heard since, Paris, by no set contrivance, but of its own impulsive emotion, was a fairy-land of blazing illumination from end to end, and ten thousand thronged cities in Europe and Asia and America shouted aloud and held festival at the news of the world’s release.

I lingered in London ten days, serving as a special constable. I dreaded to go back to my house, desolate among the ashes of Maybury Hill, the house in which I had hoped to live the best part of my days. I believed my wife was dead. I feared to find a solitude that should confirm my fears. But at last, I induced myself to resign my white badge and staff and return by one of the Government trains, by which people were taken back free of charge to their proper dwelling places. The Surrey country was pitifully scarred and blackened on either side, and every watercourse was scarlet with the red weed.

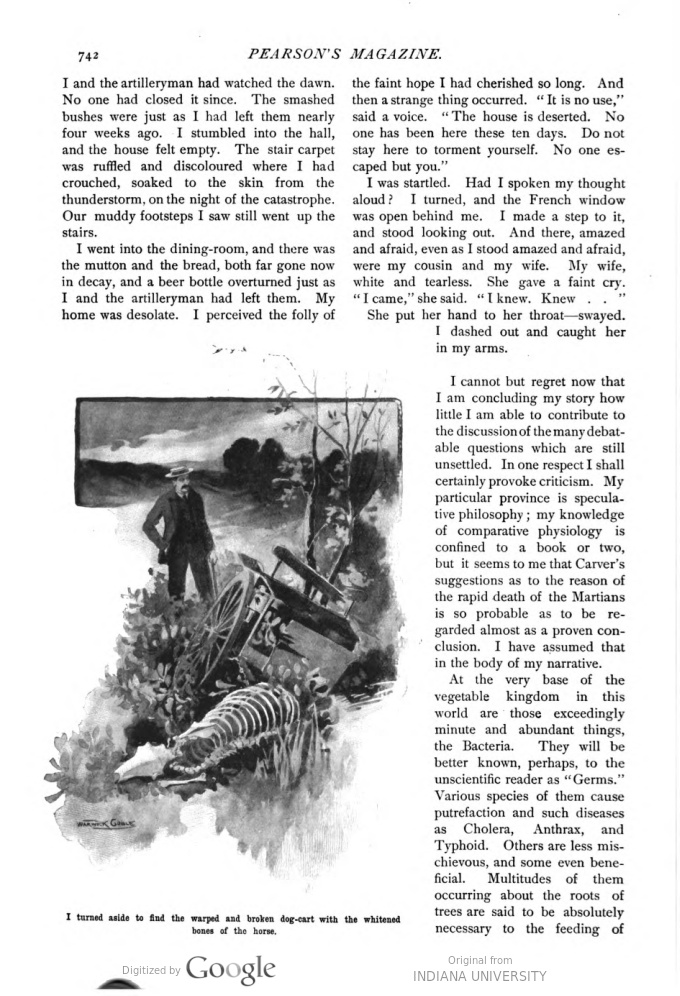

I descended at Byfleet station and took the road to Maybury, past the place where I and the artilleryman had talked to the hussars, and on by the spot where the Martian had appeared to me in the thunderstorm. Here, I turned aside to find, among a tangle of red fronds, the warped and broken dog-cart with the whitened bones of the horse, scattered and gnawed. Then I returned through the pine wood, neck high with weed here and there, to find that the landlord of the ‘Spotted Dog’ had already found burial, and so home, past the College Arms. A man standing at an open cottage door greeted me by name as I passed.

I looked at my house with a quick flash of hope that faded immediately. The door had been forced; it was unfastened and was opening slowly as I approached. Then it slammed again. The curtains of my study fluttered out of the open window from which [text marker: end page 741]

[text marker: start page 742] I and the artilleryman had watched the dawn. No one had closed it since. The smashed bushes were just as I had left them nearly four weeks ago. I stumbled into the hall, and the house felt empty. The stair carpet was ruffled and discoloured where I had crouched, soaked to the skin from the thunderstorm, on the night of the catastrophe. Our muddy footsteps I saw still went up the stairs.

I went into the dining-room, and there was the mutton and the bread, both far gone now in decay, and a beer bottle overturned just as I and the artilleryman had left them. My home was desolate. I perceived the folly of the faint hope I had cherished so long. And then a strange thing occurred. “It is no use,” said a voice. “The house is deserted. No one has been here these ten days. Do not stay here to torment yourself. No one escaped but you.”

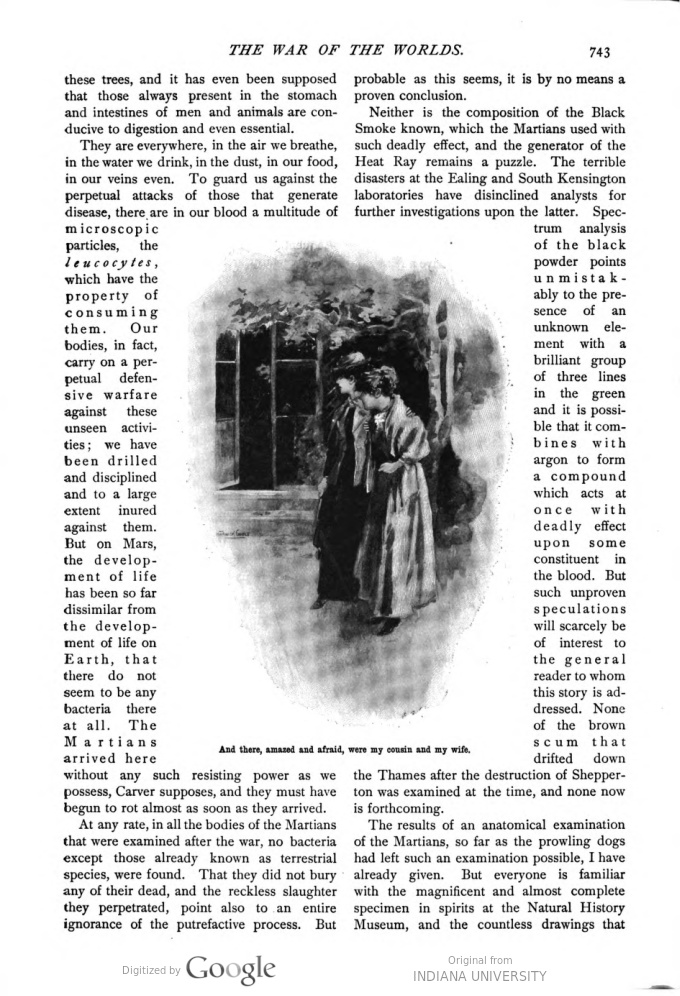

I was startled. Had I spoken my thought aloud? I turned, and the French window was open behind me. I made a step to it, and stood looking out. And there, amazed and afraid, even as I stood amazed and afraid, were my cousin and my wife. My wife, white and tearless. She gave a faint cry. “I came,” she said. “I knew. Knew . . ”

She put her hand to her throat—swayed. I dashed out and caught her in my arms.

*

I cannot but regret now that I am concluding my story how little I am able to contribute to the discussion of the many debatable questions which are still unsettled. In one respect I shall certainly provoke criticism. My particular province is speculative philosophy; my knowledge of comparative physiology is confined to a book or two, but it seems to me that Carver’s suggestions as to the reason of the rapid death of the Martians is so probable as to be regarded almost as a proven conclusion. I have assumed that in the body of my narrative.

At the very base of the vegetable kingdom in this world are those exceedingly minute and abundant things, the Bacteria. They will be better known, perhaps, to the unscientific reader as “Germs.” Various species of them cause putrefaction and such diseases as Cholera, Anthrax, and Typhoid. Others are less mischievous, and some even beneficial. Multitudes of them occurring about the roots of trees are said to be absolutely necessary to the feeding of [text marker: end page 742]

[text marker: start page 743] these trees, and it has even been supposed that those always present in the stomach and intestines of men and animals are conducive to digestion and even essential.

They are everywhere, in the air we breathe, in the water we drink, in the dust, in our food, in our veins even. To guard us against the perpetual attacks of those that generate disease, there are in our blood a multitude of microscopic particles, the leucocytes, which have the property of consuming them. Our bodies, in fact, carry on a perpetual defensive warfare against these unseen activities; we have been drilled and disciplined and to a large extent inured against them. But on Mars, the development of life has been so far dissimilar from the development of life on Earth, that there do not seem to be any bacteria there at all. The Martians arrived here without any such resisting power as we possess, Carver supposes, and they must have begun to rot almost as soon as they arrived.

At any rate, in all the bodies of the Martians that were examined after the war, no bacteria except those already known as terrestrial species, were found. That they did not bury any of their dead, and the reckless slaughter they perpetrated, point also to an entire ignorance of the putrefactive process. But probable as this seems, it is by no means a proven conclusion.

Neither is the composition of the Black Smoke known, which the Martians used with such deadly effect, and the generator of the Heat Rays remains a puzzle. The terrible disasters at the Ealing and South Kensington laboratories have disinclined analysts for further investigations upon the latter. Spectrum analysis of the black powder points unmistakably to the presence of an unknown element with a brilliant group of three lines in the green and it is possible that it combines with argon to form a compound which acts at once with deadly effect upon some constituent in the blood. But such unproven speculations will scarcely be of interest to the general reader to whom this story is addressed. None of the brown scum that drifted down the Thames after the destruction of Shepperton was examined at the time, and now none is forthcoming.

The results of an anatomical examination of the Martians, so far as the prowling dogs had left such an examination possible, I have already given. But everyone is familiar with the magnificent and almost complete specimen in spirits at the Natural History Museum, and the countless drawings that [text marker: end page 743]

[text marker: start page 744] have been made from it; and beyond that the interest of the physiology and structure is purely scientific.

It has often been asked why the Martians did not fly immediately after their arrival. They certainly did use a flying apparatus for several days, but only for brief flights of a score or so of miles, in order to reconnoitre and spread their black powder. The framework found at Kilburn was certainly this flying machine. I never saw this thing flying myself, but my brother, as I have already told in its proper place, had just a glimpse of it. It is hard to believe, seeing their other power, that this was their limit in this direction.

Two things must have prevented the immediate resort to aeronautics. In the first place it must have been impossible to pack the necessary wings in to the cylinder by which the Martians came, and in the next the problem of flying our atmosphere was one they could scarcely calculate in detail upon Mars, since it would be almost impossible for them to estimate the density of our lower air, until they reached it. But these are of course merely suggestions. The fact remains, that they did not fly fifty miles from London all through the war. Had they done so, then the destruction they would have caused must have been infinitely greater than it was, though it could not have averted the end, of course, even by a day.

A question of graver and universal interest is the possibility of another attack from the Martians. I do not think that nearly enough attention has been given to this aspect of the matter. At present the planet Mars is in conjunction, but with every return to opposition I, for one, anticipate a renewal of their adventure. In any case we should be prepared. It seems to me that it should be possible to define the position of the gun from which the shots are discharged, to keep a sustained watch upon this part of the planet, and to anticipate the arrival of the next attack.

In that case the cylinder might be destroyed with dynamite or artillery before it was sufficiently cool for the Martians to emerge, or they might be butchered by means of guns so soon as the screw opened. It seems to me that they have lost a vast advantage in the failure of their first surprise. Possibly they see it in the same light.

Lessing has advanced excellent reasons for supposing that the Martians have actually succeeded in effecting a landing on the planet Venus. Seven months ago now Venus and Mars were in alignment with the sun, that is to say, Mars was in opposition from the point of view of an observer on Venus. Subsequently a peculiar luminous and sinuous marking appeared on the unillumined half of the inner planet, and almost simultaneously a faint dark mark of a similar sinuous character was detected upon a photograph of the Martian disc. One needs to see the drawings of these appearances in order to appreciate fully their remarkable resemblance in character. The photographs were reproduced in Knowledge in July of last year; Lessing’s sketch of the luminous marks on Venus appeared in the corresponding column of Nature in the previous April.

At any rate, whether we expect another invasion or not, our views of the human future must be greatly modified by these events. We have learned now that we cannot regard this planet as being fenced in and a secure abiding place for Man; we can never anticipate the unseen good or evil that may come upon us suddenly out of space. It may be that in the larger design of the universe this invasion from Mars is not without its ultimate benefit for men; it has robbed us of that serene confidence in the future which is the most fruitful source of decadence, and it has done much to promote the conception of the commonweal of mankind. It may be that across the immensity of space the Martians have watched the fate of these pioneers of theirs and learned their lesson, and that on the planet Venus they have found a securer settlement. Be that as it may, for many years yet there will certainly be no relaxation of the eager scrutiny of the Martian disc, and those fiery darts of the sky, the shooting stars, will bring with them as they fall an unavoidable apprehension to all the sons of men.

The broadening of men’s views that has resulted can scarcely be exaggerated. Before the cylinder fell there was a general persuasion that through all the deep of space no [text marker: end page 744]

[text marker: start page 745] life existed beyond the petty surface of our minute sphere. Now we see further. If the Martians can reach Venus, there is no reason to suppose that the thing is impossible for men, and when the slow cooling of the sun makes this earth uninhabitable, it may be that the thread of life that has begun here will have streamed out and caught our sister planet within its toils. Should we conquer? Dim and wonderful is the vision I have conjured up in my mind of life spreading slowly from this little seed bed of the solar system throughout the inanimate vastness of sidereal space. But that is a remote dream. It may be, on the other hand, that the destruction of the Martians is only a reprieve. To them and not to us perhaps is the future ordained.

For my own part, the stress and danger of the time have left an abiding sense of doubt and insecurity in my mind. I sit in my study writing by lamplight, and suddenly I see again the healing valley below set with writhing flames, and feel the house behind and about me empty and desolate. I go out into the Byfleet Road and vehicles pass me, a butcher boy in a cart, a cabful of visitors, a workman on a bicycle, children going to school, and suddenly they become vague and unreal, and I hurry again with the artilleryman through the hot brooding silence. Of a night I see the black powder darkening the silent streets, and the contorted bodies shrouded in that layer; they rise upon me tattered and dog-bitten. They gibber and grow fiercer, paler, uglier, mad distortions of humanity at last, and I wake cold and wretched in the darkness of the night.

I go to London and see the busy multitudes in Fleet Street and the Strand, and it comes across my mind that they are but the ghosts of the past haunting the streets that I have seen silent and wretched, going to and fro, phantasms in a dead city, the mockery of life in a galvanised body. And strange, too, it is to stand on Primrose Hill, as I did but a day before writing this last chapter, to see the great province of houses, dim and blue through the haze of the smoke and mist, vanishing at last into the vague lower sky, to see the people walking to and fro among the flower beds on the hill, to see the sightseers about the Martian machine that stands there still, to hear the tumult of playing children, and to recall the time when I saw it all bright and clear cut, hard and silent, under the dawn of that last great day. . .

And strangest of all is it to hold my wife’s hand again, and to think that I have counted her and that she has counted me, among the dead.

THE END.

[text marker: end page 745, end installment 9]