Note: This page has been annotated with critical, historical, and cultural notes using the web annotation tool Hypothesis. You may view these annotations in the sidebar on the right-hand side of this page. Use the arrow icon to minimize the sidebar. A text-to-speech compatible transcript of the annotations for this page is available here.

The War of the Worlds in Pearson’s Magazine

Installment 7 of 9 (October 1897)

Pages from Pearson’s Magazine courtesy of HathiTrust, digitized by Google from originals at Indiana University.

[text marker: start page 447]

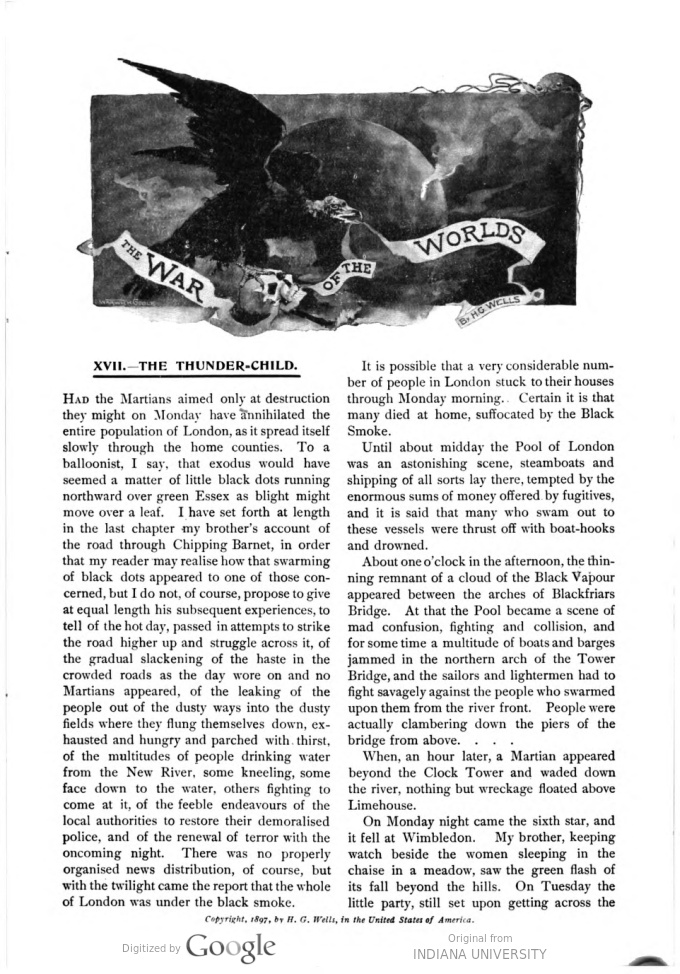

THE WAR OF THE WORLDS

BY H. G. WELLS

XVII.―THE “THUNDER CHILD”.

Had the Martians aimed only at destruction they might on Monday have annihilated the entire population of London, as it spread itself slowly through the home counties. To a balloonist, I say, that exodus would have seemed a matter of little black dots running northward over green Essex as blight might over a leaf. I have set forth at length in the last chapter my brother’s account of the road through Chipping Barnet, in order that my reader may realise how that swarming of black dots appeared to one of those concerned, but I do not, of course, propose to give at equal length his subsequent experiences, to tell of the hot day, passed in attempts to strike the road higher up and struggle across it, of the gradual slackening of the haste in the crowded roads as the day wore on and no Martians appeared, of the leaking of the people out of the dusty ways into the dusty fields where they flung themselves down, exhausted and hungry and parched with thirst, of the multitudes of people drinking water from the New River, some kneeling, some face down to the water, others fighting to come at it, of the feeble endeavours of the local authorities to restore their demoralised police, and of the renewal of terror with the oncoming night. There was no properly organised news distribution, of course, but with the twilight came the report that the whole of London was under the black smoke.

It is possible that a very considerable number of people in London stuck to their houses through Monday morning. Certain it is that many died at home, suffocated by the Black Smoke.

Until about midday the Pool of London was an astonishing scene, steamboats and shipping of all sorts lay there, tempted by the enormous sums of money offered by fugitives, and it is said that many who swam out to these vessels were thrust off with boat-hooks and drowned.

About one o’clock in the afternoon, the thinning remnant of a cloud of the Black Vapour appeared between the arches of Blackfriars Bridge. At that the Pool became a scene of mad confusion, fighting and collision, and for some time a multitude of boats and barges jammed in the northern arch of the Tower Bridge, and the sailors and lightermen had to fight savagely against the people who swarmed upon them from the river front. People were actually clambering down the piers of the bridge from above….

When, an hour later, a Martian appeared beyond the Clock Tower and waded down the river, nothing but wreckage floated above Limehouse.

On Monday night came the sixth star, and it fell at Wimbledon. My brother, keeping watch beside the women sleeping in the chaise in a meadow, saw the green flash of it fall beyond the hills. On Tuesday the little party, still set upon getting across the [text marker: end page 447]

[text marker: start page 448] sea, made its way through the swarming country towards Colchester. The news that the Martians were now in possession of the whole of London was confirmed. They had been seen at Highgate and even it was said at Neasden. But they did not come into my brother’s view that day. That day the scattered multitudes began to realise the urgent need of provisions. As they grew hungry the rights of property ceased to be regarded.

Farmers were out to defend the cattle sheds, granaries, and ripening root crops, with arms in their hands. A number of people now, like my brother, had their faces eastward, and there were some desperate souls even going back towards London to get food. These were chiefly people from the northern suburbs, whose knowledge of the Black Smoke came by hearsay. He heard that about half the members of the Government had gathered at Birmingham, and that enormous quantities of high explosives were being prepared to be used in automatic mines across the Midland counties.

He was also told that the Midland Railway Company had replaced the desertions of the first day’s panic, had resumed traffic, and were running northward trains from St. Albans to relieve the congestion of the home counties. There was also a placard in Chipping Ongar announcing that large stores of flour were available in the northern towns and that within twenty-four hours bread would be distributed among the starving people in the neighbourhood. But this intelligence did not deter him from the plan of escape he had formed, and the three pressed eastward all day, and saw no more of the bread distribution than this promise. Nor, as a matter of fact, did anyone else see more of it. That night fell the seventh star, falling upon Primrose Hill. It fell while Miss Elphinstone was watching, for she took that duty alternately with my brother. She saw it.

On Wednesday the three fugitives—they had passed the night in a field of unripe wheat—reached Chelmsford, and a body of the inhabitants calling itself the Committee of Public Supply, promptly seized the pony as provisions, and would give nothing in exchange for it but the promise of a share in it the next day. Here there were rumours of Martians at Epping, and news of the destruction of Waltham Abbey Powder Mills in a vain attempt to blow up one of the invaders.

People were watching for Martians here from the church towers. My brother, very luckily for him as it chanced, preferred to push on at once to the coast, rather than wait for food, although all three of them were very hungry. By midday they passed through Tillingham, which was, strangely enough, absolutely silent and deserted, save for a few plundering fugitives, who were hunting for food: and so they came in sight of the sea, and the most amazing crowd of shipping of all sorts that it is possible to imagine.

For after the sailors could no longer come up the Thames, they came on to the Essex coast, to Harwich, and Walton, and Clacton, and afterwards to Foulness and Shoebury, to bring off the people. They lay in a huge sickle-shaped curve that vanished into mist at last towards the Naze. Close inshore was a multitude of fishing-smacks, English, Scotch, French, Dutch, and even Swedish; steam launches from the Thames, yachts, electric boats; and beyond were ships of larger burthen, a multitude of filthy colliers, trim merchantmen, cattle ships, passenger boats, petroleum tanks, ocean tramps, an old white transport even, neat white and grey liners from Southampton and Hamburg; and along the blue coast across the Blackwater my brother could make out dimly a dense swarm of boats chaffering with the people on the beach, a swarm which also extended up the Blackwater almost to Maldon.

About a couple of miles out lay an ironclad very low in the water, almost, to my brother’s perception, like a water-logged ship. This was the ram Thunder Child. It was the only warship in sight, but far away to the right over the smooth surface of the sea—for that day there was a dead calm—lay a serpent of black smoke to mark the next ironclads of the Channel Fleet, which hovered in an extended line, steam up and ready for action, across the Thames estuary during the course of the Martian conquest, vigilant and yet powerless to prevent it.

At the sight of the sea Mrs. Elphinstone, in spite of the assurances of her sister-in-law, gave way to panic. She had never been out [text marker: end page 448]

[text marker: start page 449] of England before, she would rather die than trust herself friendless in a foreign country, and so forth. She seemed, poor woman, to imagine that the French and the Martians might prove very similar. She had been growing increasingly hysterical, fearful and depressed, during the two days’ journeyings.

Her great idea was to return to Stanmore. Things had always been well and safe at Stanmore. They would find George at Stanmore…. It was with the greatest difficulty they could get her down to the beach, where presently my brother succeeded in attracting the attention of the men on a paddle-steamer out of the Thames. They sent a boat and drove a bargain for thirty-six pounds for the three. The steamer was going, these men said, to Ostend.

It was about two o’clock when my brother, having paid their fares at the gangway, found himself safely aboard the steamboat with his charges. There was food aboard, albeit at exorbitant prices, and the three of them contrived to eat a meal on one of the seats forward.

There were already a couple of score of passengers aboard, some of whom had expended their last money in securing a passage, but the captain lay off the Blackwater until five in the afternoon, picking up passengers the whole time until the seated decks were even dangerously crowded. He would probably have remained longer, had it not been for the sound of guns that began about that hour in the south. As if in answer, the ironclad seaward fired a small gun and hoisted a string of flags. A jet of smoke sprang out of her funnels.

Some of the passengers were of opinion that this firing came from Shoeburyness, until it was noticed that it was growing louder. At the same time, far away in the south-east the masts and upperworks of three ironclads rose one after the other out of the sea, beneath clouds of black smoke. But my brother’s attention speedily reverted to the distant firing in the south. He fancied he saw a column of smoke rising out of the distant grey haze.

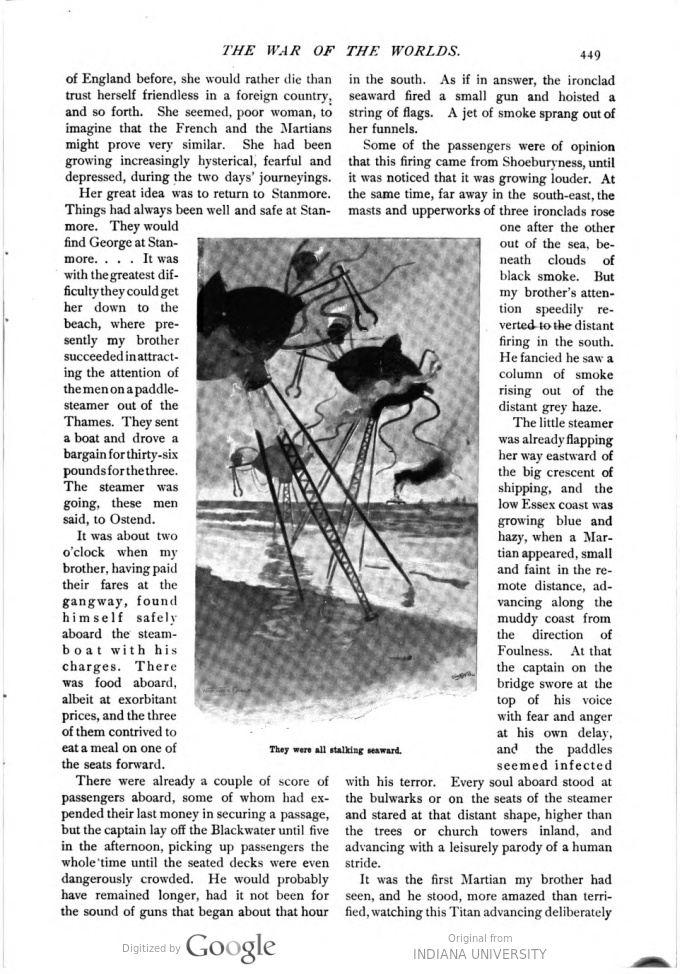

The little steamer was already flapping her way eastward of the big crescent of shipping, and the low Essex coast was growing blue and hazy, when a Martian appeared, small and faint in the remote distance, advancing along the muddy coast from the direction of Foulness. At that the captain on the bridge swore at the top of his voice with fear and anger at his own delay, and the paddles seemed infected with his terror. Every soul aboard stood at the bulwarks or on the seats of the steamer and stared at that distant shape, higher than the trees or church towers inland, and advancing with a leisurely parody of a human stride.

It was the first Martian my brother had seen, and he stood, more amazed than terrified, watching this Titan advancing deliberately [text marker: end page 449]

[text marker: start page 450] towards the shipping, wading farther and farther into the water as the coast fell away. Then, far away beyond the Crouch, came another striding over some stunted trees, and then yet another, still farther off, wading deeply through a shiny mudflat that seemed to hang halfway up between sea and sky. They were all stalking seaward, as if to intercept the escape of the multitudinous vessels that were crowded between Foulness and the Naze. In spite of the throbbing exertions of the engines of the little paddle boat, and the pouring foam that her wheels flung behind her, she receded with terrifying slowness from this ominous advance.

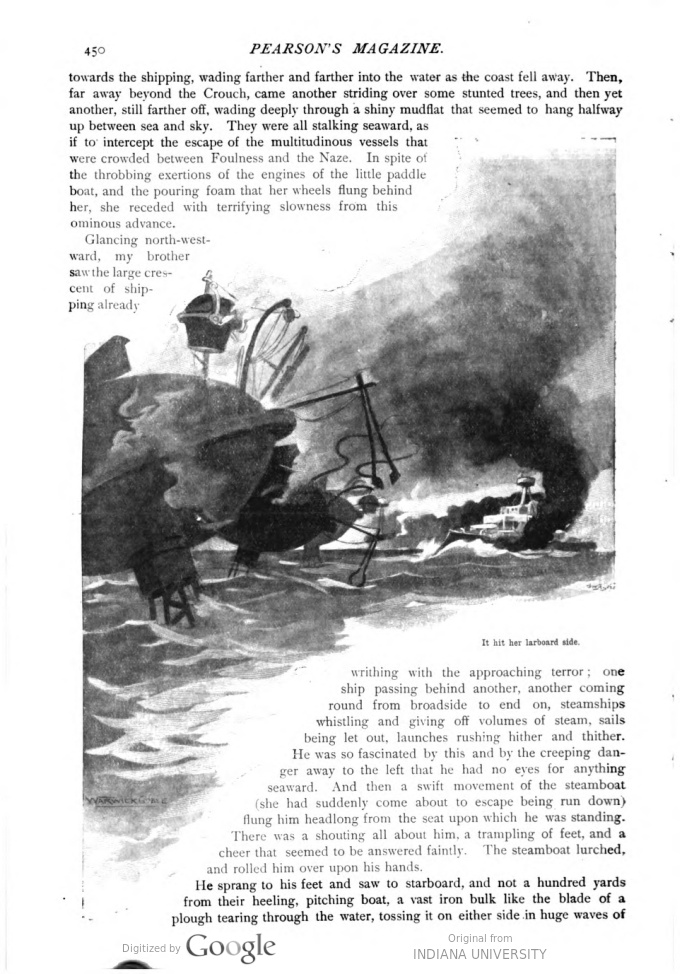

Glancing north-westward, my brother saw the large crescent of shipping already writhing with the approaching terror; one ship passing behind another, another coming round from broadside to end on, steamships whistling and giving off volumes of steam, sails being let out, launches rushing hither and thither. He was so fascinated by this and by the creeping danger away to the left that he had no eyes for anything seaward. And then a swift movement of the steamboat (she had suddenly come about to escape being run down) flung him headlong from the seat upon which he was standing. There was a shouting all about him, a trampling of feet, and a cheer that seemed to be answered faintly. The steamboat lurched, and rolled him over upon his hands.

He sprang to his feet and saw to starboard, and not a hundred yards from their heeling, pitching boat, a vast iron bulk like the blade of a plough tearing through the water, tossing it on either side in huge waves of [text marker: end page 450]

[text marker: start page 451] foam that leapt towards the steamer, flinging her paddles helplessly in the air and then sucking her deck down almost to the water line.

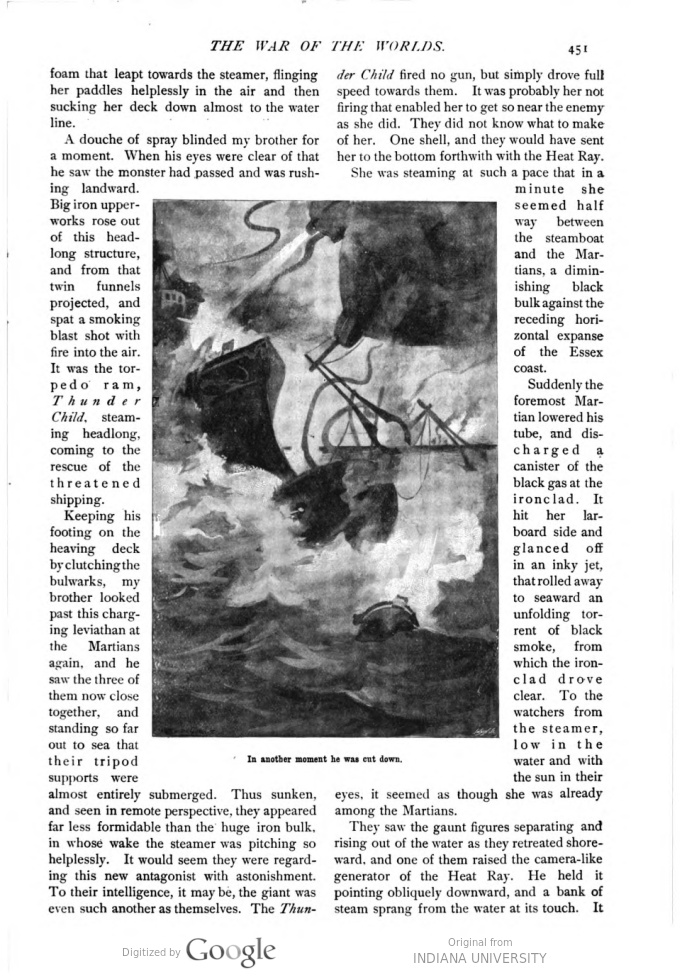

A douche of spray blinded my brother for a moment. When his eyes were clear of that he saw the monster had passed and was rushing landward. Big iron upper-works rose out of this headlong structure, and from that twin funnels projected, and spat a smoking blast shot with fire into the air. It was the torpedo ram, Thunder Child, steaming headlong, coming to the rescue of the threatened shipping.

Keeping his footing on the heaving deck by clutching the bulwarks, my brother looked past this charging leviathan at the Martians again, and he saw the three of them now close together, and standing so far out to sea that their tripod supports were almost entirely submerged. Thus sunken, and seen in remote perspective, they appeared far less formidable than the huge iron bulk, in whose wake the steamer was pitching so helplessly. It would seem they were regarding this new antagonist with astonishment. To their intelligence, it may be, the giant was even such another as themselves. The Thunder Child fired no gun, but simply drove full speed towards them. It was probably her not firing that enabled her to get so near the enemy as she did. They did not know what to make of her. One shell, and they would have sent her to the bottom forthwith with the Heat Ray.

She was steaming at such a pace that in a minute she seemed half way between the steamboat and the Martians, a diminishing black bulk against the receding horizontal expanse of the Essex coast.

Suddenly the foremost Martian lowered his tube, and discharged a canister of the black gas at the ironclad. It hit her larboard side and glanced off in an inky jet, that rolled away to seaward an unfolding torrent of black smoke, from which the ironclad drove clear. To the watchers from the steamer, low in the water and with the sun in their eyes, it seemed as though she was already among the Martians.

They saw the gaunt figures separating and rising out of the water as they retreated shoreward, and one of them raised the camera-like generator of the Heat Ray. He held it pointing obliquely downward, and a bank of steam sprang from the water at its touch. It [text marker: end page 451]

[text marker: start page 452] must have driven through the iron of the ship’s side like a white-hot iron rod through paper.

A flicker of flame went up through the rising steam, and then the Martian reeled and staggered. In another moment he was cut down, and a great body of water and steam shot high in the air. The guns of the Thunder Child sounded through the reek going off one after the other, and one shot splashed the water high close by the steamer, ricocheted towards the other flying ships to the north and smashed a smack to matchwood.

But no one heeded that very much. At the sight of the Martian’s collapse the captain on the bridge yelled inarticulately and all the crowding passengers on the steamer’s stern shouted together. And then they yelled again. For surging out beyond the white tumult, drove something long and black, the flames streaming from its middle parts, its ventilators and funnels spouting fire.

She was alive still—the steering gear, it seems, was intact and her engines working. She headed straight for a second Martian, and was within a hundred yards of him when the Heat Ray came to bear. Then with a violent thud, a blinding flash, her decks, her funnels, leapt upward. The Martian staggered with the violence of her explosion, and in another moment the flaming wreckage, still driving forward with the impetus of its pace, had struck him and crumpled him up like a thing of cardboard. My brother shouted involuntarily. A boiling tumult of steam hid everything again.

“Two!” yelled the captain. Everyone was shouting—the whole steamer from end to end rang with frantic cheering that was taken up first by one and then by all in the crowding multitude of ships and boats that was driving out to sea.

The steam hung upon the water for many minutes, hiding the third Martian and the coast altogether. And all this time the boat was paddling steadily out to sea and away from the fight; and when at last the confusion cleared, the drifting bank of black vapour intervened, and nothing of the Thunder Child could be made out, nor could the third Martian be seen. But the ironclads to seaward were now quite close and standing in towards shore past the steamboat.

The little vessel continued to beat its way seaward, and the ironclads receded slowly towards the coast, which was hidden still by a marbled bank of vapour, part steam, part black gas eddying and combining in the strangest ways. The fleet of refugees was scattering to the north-east, several smacks were sailing between the ironclads and the steamboat. After a time, and before they reached the sinking cloud bank, the warships turned northward, and then abruptly went about and passed into the thickening haze of evening southward. The coast grew faint, and at last indistinguishable amid the low banks of clouds that were gathering about the sinking sun.

Then suddenly out of the golden haze of the sunset came the vibration of guns, and a form of black shadows moving. Everyone struggled to the rail of the steamer and peered into the blinding furnace of the west, but nothing was to be distinguished clearly. A mass of smoke rose slantingly and barred the face of the sun.

The steamboat throbbed on its way through an interminable suspense. The sun sank into grey clouds, the sky flushed and darkened, the evening star trembled into sight.

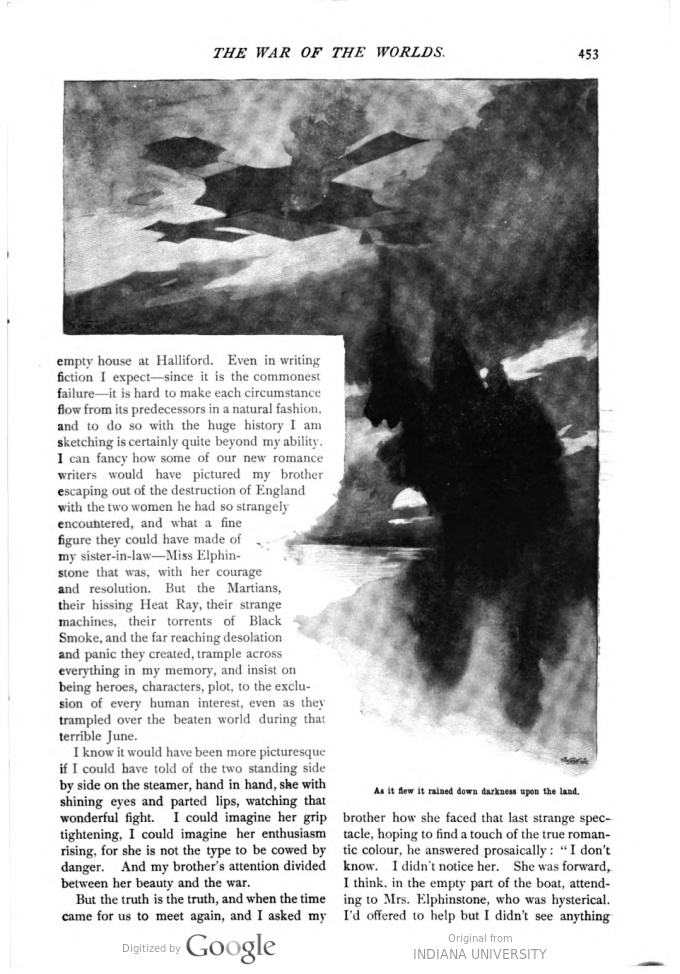

It was deep twilight when the captain cried out and pointed. My brother strained his eyes. Something rushed up into the sky out of the greyness, rushed slantingly upward and very swiftly into the luminous clearness above the clouds in the western sky, something flat and broad and very large, that swept round in a vast curve, grew smaller, sank slowly, and vanished again into the grey mystery of the night. And as it flew it rained down darkness upon the land.

XVIII.—LONDON UNDER THE MARTIANS.

My inexpertness as a story writer insists on appearing. I have wandered away from my own adventures to tell of the experiences of my brother, and for all these last chapters I and the curate have still been lurking in the [text marker: end page 452]

[text marker: start page 453] empty house at Halliford. Even in writing fiction I expect—since it is the commonest failure—it is hard to make each circumstance flow from its predecessors in a natural fashion, and to do so with the huge history I am sketching is certainly quite beyond my ability. I can fancy how some of our new romance writers would have pictured my brother escaping out of the destruction of England with the two women he had so strangely encountered, and what a fine figure they could have made of my sister-in-law—Miss Elphinstone that was, with her courage and resolution. But the Martians, their hissing Heat Ray, their strange machines, their torrents of Black Smoke, and the far reaching desolation and panic they created, trample across everything in my memory, and insist on being heroes, characters, plot, to the exclusion of every human interest, even as they trampled over the beaten world during that terrible June.

I know it would have been more picturesque if I could have told of the two standing side by side on the steamer, hand in hand, she with shining eyes and parted lips, watching that wonderful fight. I could imagine her grip tightening, I could imagine her enthusiasm rising, for she is not the type to be cowed by danger. And my brother’s attention divided between her beauty and the war.

But the truth is the truth, and when the time came for us to meet again, and I asked my brother how she faced that last strange spectacle, hoping to find a touch of the true romantic colour, the answered prosaically: “I don’t know. I didn’t notice her. She was forward, I think, in the empty part of the boat, attending to Mrs. Elphinstone, who was hysterical. I’d offered to help but I didn’t see anything [text marker: end page 453]

[text marker: start page 454] that I could do, so I went aft to watch the fight.” So poor Romance, with its craving for situations, goes down under the pitiless heels of fact.

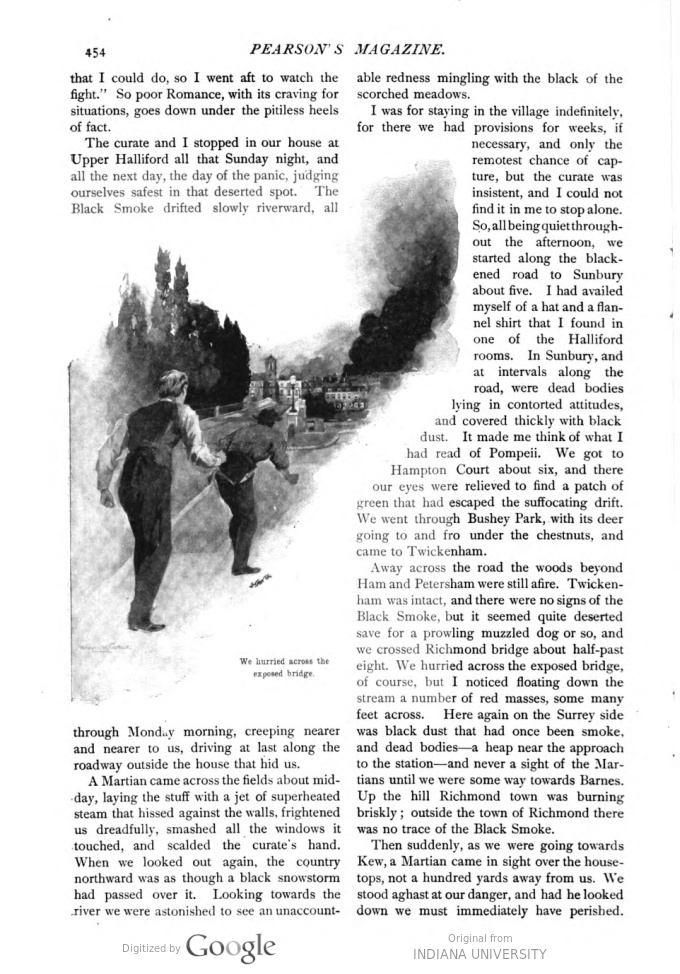

The curate and I stopped in our house at Upper Halliford all that Sunday night, and all the next day, the day of the panic, judging ourselves safest in that deserted spot. The Black Smoke drifted slowly riverward, all through Monday morning, creeping nearer and nearer to us, driving at last along the roadway outside the house that hid us.

A Martian came across the fields about midday, laying the stuff with a jet of superheated steam that hissed against the walls, frightened us dreadfully, smashed all the windows it touched, and scalded the curate’s hand. When we looked out again, the country northward was as though a black snowstorm had passed over it. Looking towards the river we were astonished to see an unaccountable redness mingling with the black of the scorched meadows.

I was for staying in the village indefinitely, for there we had provisions for weeks, if necessary, and only the remotest chance of capture, but the curate was insistent, and I could not find it in me to stop alone. So, all being quiet throughout the afternoon, we started along the blackened road to Sunbury about five. I had availed myself of a hat and a flannel shirt that I found in one of the Halliford rooms. In Sunbury, and at intervals along the road, were dead bodies lying in contorted attitudes, and covered thickly with black dust. It made me think of what I had read of Pompeii. We got to Hampton Court about six, and there our eyes were relieved to find a patch of green that had escaped the suffocating drift. We went through Bushey Park, with its deer going to and fro under the chestnuts, and came to Twickenham.

Away across the road the woods beyond Ham and Petersham were still afire. Twickenham was intact, and there were no signs of the Black Smoke, but it seemed quite deserted save for a prowling muzzled dog or so, and we crossed Richmond bridge about half past eight. We hurried across the exposed bridge, of course, but I noticed floating down the stream a number of red masses, some many feet across. Here again on the Surrey side was black dust that had once been smoke, and dead bodies—a heap near the approach to the station—and never a sight of the Martians until we were some way towards Barnes. Up the hill Richmond town was burning briskly; outside the town of Richmond there was no trace of the Black Smoke.

Then suddenly, as we going towards Kew, came a Martian came in sight over the housetops, not a hundred yards away from us. We stood aghast at our danger, and had he looked down we must immediately have perished. [text marker: end page 454]

[text marker: start page 455] We were so terrified that we dared not go on, but turned aside and hid in a tool-shed in a garden. From Halliford to this place we must have tramped a dozen miles or more, and never a living man had we seen all that time except once at Richmond—a group of three people, with their backs to us, running down a side street towards the river.

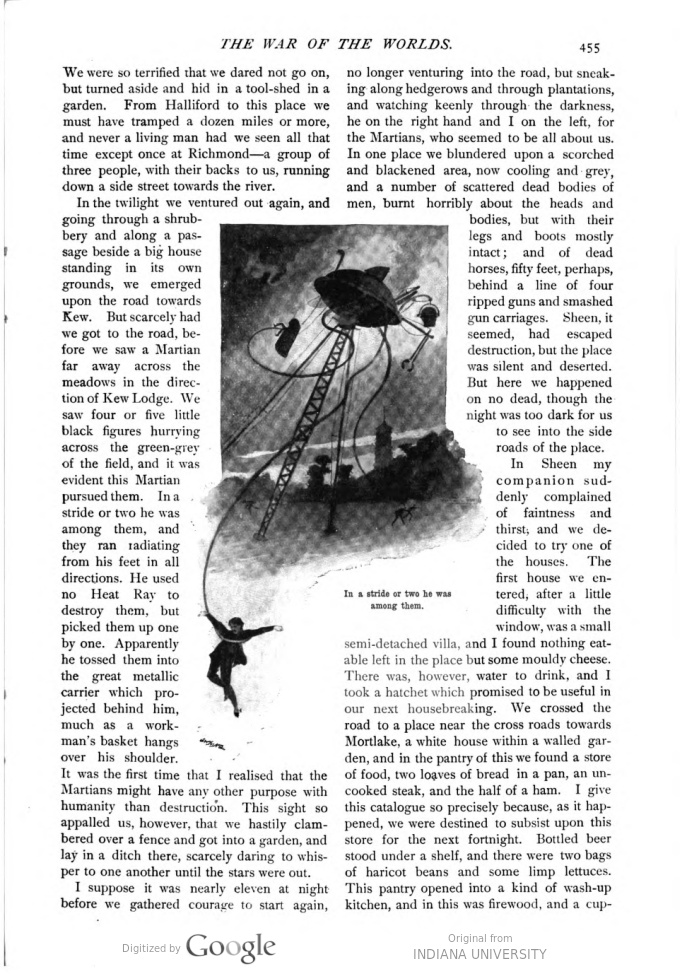

In the twilight we ventured out again, and going through a shrubbery and along a passage beside a big house standing in its own grounds, we emerged upon the road towards Kew. But scarcely had we got to the road, before we saw a Martian far away across the meadows in the direction of Kew Lodge. We saw four or five little black figures hurried before it across the green-grey of the field, and it was evident this Martian pursued them. In a stride or two he was among them, and they ran radiating from his feet in all directions. He used no Heat Ray to destroy them, but picked them up one by one. Apparently he tossed them into the great metallic carrier which projected behind him, much as a workman’s basket hangs over his shoulder. It was the first time that I realised that the Martians might have any other purpose with humanity than destruction. This sight so appalled us, however, that we hastily clambered over a fence and got into a garden, and lay in a ditch there, scarcely daring to whisper to one another until the stars were out.

I suppose it was nearly eleven at night before we gathered courage to start again, no longer venturing into the road, but sneaking along hedgerows and through plantations, and watching keenly through the darkness, he on the right hand and I on the left, for the Martians, who seemed to be all about us. In one place we blundered upon a scorched and blackened area, now cooling and grey, and a number of scattered dead bodies of men, burnt horribly about the heads and bodies, but with their legs and boots mostly intact; and of dead horses, fifty feet, perhaps, behind a line of four ripped guns and smashed gun carriages. Sheen, it seemed, had escaped destruction, but the place was silent and deserted. But here we happened on no dead, though the night was too dark for us to see into the side roads of the place.

In Sheen my companion suddenly complained of faintness and thirst, and we decided to try one of the houses. The first house we entered, after a little difficulty with the window, was a small semi-detached villa, and I found nothing eatable left in the place but some mouldy cheese. There was, however, water to drink, and I took a hatchet which promised to be useful in our next housebreaking. We crossed the road to a place near the cross roads towards Mortlake, a white house within a walled garden, and in the pantry of this we found a store of food, two loaves of bread in a pan, an uncooked steak, and the half of a ham. I give this catalogue so precisely because, as it happened, we were destined to subsist upon this store for the next fortnight. Bottled beer stood under a shelf, and there were two bags of haricot beans and some limp lettuces. This pantry opened into a kind of wash-up kitchen, and in this was firewood, and a cup-[text marker: end page 455 in the middle of the word “cupboard”]

[text marker: start page 456 in the middle of the word “cupboard” ] board in which we found nearly a dozen of Burgundy, tinned soups and salmon, and two tins of biscuits.

We sat in the adjacent kitchen—in the dark, for we dared not strike a light—and ate bread and ham and drank beer out of one bottle. The curate, who was still timorous and restless, was for pushing on, and I was urging him to keep up his strength by eating, when the thing that was to imprison us happened.

“It can’t be midnight yet,” I said, and then came a blinding glare of vivid green light. Everything in the kitchen leapt out, clearly visible in green and black, and then vanished again. And then followed such a concussion as I have never heard before or since. So close on the heels of this as to seem instantaneous, came a thud behind me, a clash of glass, a crash and rattle of falling masonry all about us, and incontinently the plaster of the ceiling came down upon us, smashing into a multitude of fragments upon our heads.

I was knocked headlong across the floor against the oven handle, and stunned. I was insensible for a long time, the curate told me, and when I came to we were in darkness again, and he, with a face wet, as I found afterwards, with blood from a cut forehead, was pouring water over me.

For some time I could not recollect what had happened. Then things came to me slowly. A bruise on my temple asserted itself. “Are you better?” asked the curate in a whisper again and again. At last I answered him. I sat up.

“Don’t move,” he said. “The floor is covered with smashed crockery from the dresser. You can’t possibly move without making a noise, and I fancy they are outside.”

We both sat quite silent, so that we could scarcely hear one another breathing. Everything seemed deadly still, though once something near us, some plaster or broken brickwork, slid down with a rumbling sound. Outside and very near was an intermittent, metallic rattle. “That!” said the curate when presently it happened again.

“Yes,” I said, and then, with a flash of comprehension, “I have it!”

“What is it?” “The fifth cylinder, the fifth shot from Mars, has struck this house!”

“God help us!” said the Curate.

Our situation was so strange and dangerous that for three or four hours, until the dawn came, we scarcely moved. And then the light filtered in, not through the window, which remained black, but through a triangular aperture in the wall behind us. The interior of the kitchen, which we now saw greyly for the first time, presented a strange appearance. The window had been burst in by a mass of garden mould, which flowed over the table upon which we had been sitting and lay about our feet. Outside the soil was banked high against the house. At the top of the window frame we could see an uprooted drainpipe. The floor was littered with smashed hardware. The end of the kitchen towards the house was broken into, and since the daylight shone in there it was evident the greater part of the house had collapsed. Contrasting vividly with this ruin was the neat dresser, stained a pleasant light green and with a number of burnished copper and tin vessels below it, the bright wall paper imitating blue and white tiles, and a couple of gay coloured supplements fluttering from the walls above the kitchen range.

We afterwards found the Fifth Cylinder had fallen just in front of the house, pulverising the garden wall and burying itself partly in the garden and partly in the road. The mass of the house and the displaced earth had—“splashed” is really the only possible word—over us, had behaved just like mud under the blow of a hammer. By a miracle the kitchen and scullery had stood the impact, and we were now imprisoned under an unknown quantity of soil and ruins. The scullery door was shut by tons of earth; we were shut in, in fact, in every direction except towards the cylinder. And there was a rough triangular aperture, between a beam and a heap of broken bricks, through which a dim light came, and through which we saw the body of a Martian standing sentinel, I suppose, over the still glowing cylinder.

At the sight of that we crawled as circumspectly as possible out of the twilight of the kitchen into the darkness of the scullery.

(To be continued next month.)

[text marker: end page 456, end installment 7]