As is discussed on this site’s page about Pearson’s Magazine, Pearson’s was a general-interest magazine that included in each issue serialized and short fiction, poetry, satire, essays, news, articles on art, history, science, and other cultural and social issues. As a staff illustrator, Warwick Goble was tasked with creating illustrations not only for fiction (like The War of the Worlds), but also nonfiction pieces. One such piece was “The Terrible Trades of Sheffield”: a nonfiction article by Robert Machray about steel works in Sheffield that made armor for warships. This piece appeared in the March 1897 issue of Pearson’s, which was published directly before the issue in which the first installment of The War of the Worlds appeared.

Goble created eleven illustrations for the nine-page article, depicting in vivid detail the various stages of steel production in the Sheffield factories. Based on publication timing, he likely illustrated this piece just before or during the time that he was working on The War of the Worlds. Indeed, Goble’s responses to Machray’s language and to the steel works themselves seem to have seeped into his images for Wells’s novel. The similarities between the industrial machinery in Sheffield and elements of Goble’s conception of the Martian fighting-machines suggest a direct correlation.

“The Terrible Trades of Sheffield” serves as a model case study for the difficulties that illustrated periodicals and similar texts present for text-to-speech engines. Though HathiTrust goes to great lengths to maximize the accessibility of its site, creating accessible versions of facsimiles, especially of older documents, is a monumental task. A comparison of the OCR “accessible” text from HathiTrust with a corrected transcript reveals some of the specific issues. In addition to the expected spelling and punctuation mistakes common with OCR, the positioning of image captions and the structure of columns to accommodate atypically-shaped illustrations causes text to be presented out of order or with interruptions. The title and author of the article itself are not presented in the “accessible” OCR because they are presented in an image. These same issues occur across the whole of The War of the Worlds in Pearson’s.

The full, corrected text of “The Terrible Trades of Sheffield” as it appeared in Pearson’s Magazine is presented here alongside facsimiles of the original pages with illustrations by Warwick Goble. Image captions by Madeline B. Gangnes accompany the facsimiles.

[text marker: start page 290]

THE TERRIBLE TRADES OF SHEFFIELD

BY ROBERT MACHRAY.

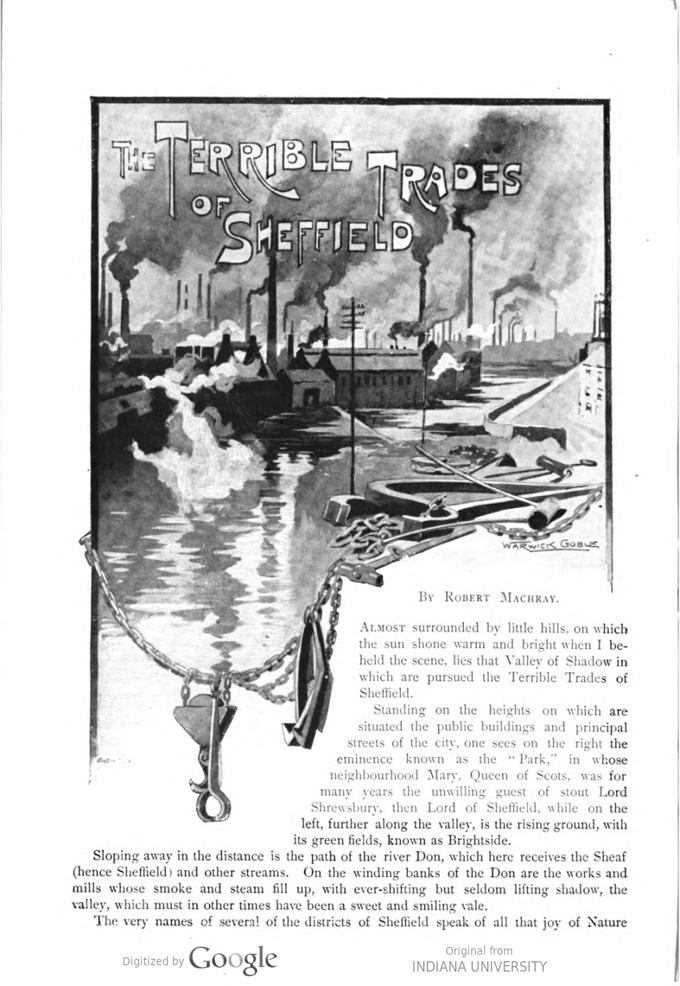

ALMOST surrounded by little hills, on which the sun shone warm and bright when I beheld the scene, lies that Valley of Shadow in which are pursued the Terrible Trades of Sheffield.

Standing on the heights on which are situated the public buildings and principal streets of the city, one sees on the right the eminence known as the “Park,” in whose neighbourhood Mary, Queen of Scots, was for many years the unwilling guest of stout Lord Shrewsbury, then Lord of Sheffield, while on the left, further along the valley, is the rising ground, with its green fields, known as Brightside.

Sloping away in the distance is the path of the river Don, which here receives the Sheaf (hence Sheffield) and other streams. On the winding banks of the Don are the works and mills whose smoke and steam fill up, with ever-shifting but seldom lifting shadow, the valley, which must in other times have been a sweet and smiling vale.

The very names of several of the districts of Sheffield speak of all that joy of Nature [text marker: end page 290]

[text marker: start page 291] which the city has well nigh lost—the price it has had to pay for its commercial and mechanical greatness. Such titles as “Daisy Walk,” “Pea Croft,” “Bower Spring,” “Balm Green,” are not without a certain pathos. But it is not easy to believe that such a designation as “Salmon Pastures,” now the site of large manufactories, ever found any justification in the inland waters of the Don.

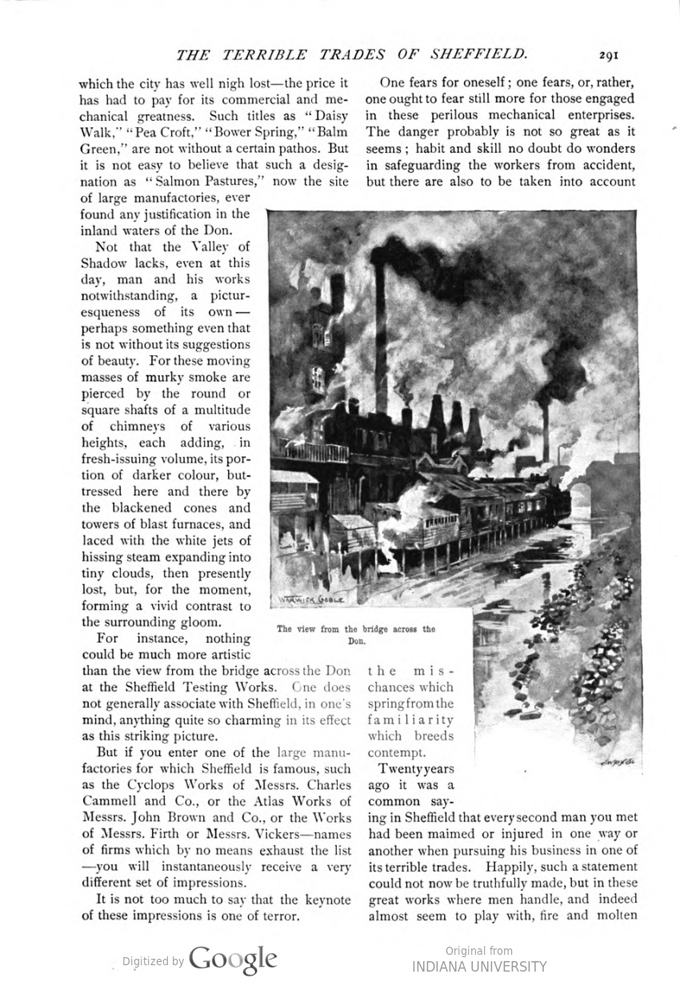

Not that the Valley of Shadow lacks, even at this day, man and his works notwithstanding, a picturesqueness of its own—perhaps something even that is not without its suggestions of beauty. For these moving masses of murky smoke are pierced by the round or square shafts of a multitude of chimneys of various heights, each adding, in fresh-issuing volume, its portion of darker colour, buttressed here and there by the blackened cones and towers of blast furnaces, and laced with the white jets of hissing steam expanding into tiny clouds, then presently lost, but, for the moment, forming a vivid contrast to the surrounding gloom.

For instance, nothing could be much more artistic than the view from the bridge across the Don at the Sheffield Testing Works. One does not generally associate with Sheffield, in one’s mind, anything quite so charming in its effect as this striking picture.

But if you enter one of the large manufactories for which Sheffield is famous, such as the Cyclops Works of Messrs. Charles Cammell and Co., or the Atlas Works of Messrs. John Brown and Co., or the Works of Messrs. Firth or Messrs. Vickers—names of firms which by no means exhaust the list—you will instantaneously receive a very different set of impressions.

It is not too much to say that the keynote of these impressions is one of terror.

One fears for oneself; one fears, or, rather, one ought to fear still more for those engaged in these perilous mechanical enterprises. The danger probably is not so great as it seems; habit and skill no doubt do wonders in safeguarding the workers from accident, but there are also to be taken into account the mischances which spring from the familiarity which breeds contempt.

Twenty years ago it was a common saying in Sheffield that every second man you met had been maimed or injured in one way or another when pursuing his business in one of its terrible trades. Happily, such a statement could not now be truthfully made, but in these great works where men handle, and indeed almost seem to play with, fire and molten [text marker: end page 291]

[text marker: start page 292] metal and blazing ingots, danger must be ever present and death, never far away. Yet the number of fatal or even serious accidents is not so great as one would have expected.

To the visitor unfamiliar with such scenes, who makes the tour for the first time of one of these vast manufactories where the steel armour for warships—barbette, casemate, or plates for the vessel’s sides—or where the great, gleaming, forty feet long cannon are made, the most prominent and insistent idea in his mind is certainly one of danger.

Scarcely has he passed from the comparative quiet of the street through the outer offices when his ears are assailed by tumultuous uproars. In a moment he steps from calm to storm. The blast of the tempest, the volley of the thunder, the flash of the lightning, seem to fall upon him at once. The whole place is one deafening, deadly menace, instinct with diabolical energy. He hesitates to move an inch.

Timidly he follows his guide, who leads the way with a smile on his face at the shrinking and solicitous manner of the visitor. The latter presently finds himself in a vast building, which, however, is only one of a series of buildings as great or even greater. Before him he sees enormous masses of machinery, gigantic hammers, huge rollers, furnaces grim and glowing, and engines of all kinds, while the crash of falling iron, the screams of the circular saws cutting through the half-molten steel amidst a blaze of golden sparks, the hissing steam, the rumbles and roars of a hundred mechanical devils, confuse and stun his senses all at once. Everywhere men are moving about, guiding, compelling, directing all this Titanic and turbulent life. Overhead are the great travelling cranes, from which depend huge claws of steel.

When he recovers himself a little he begins to notice that all the volcanic activities of the place are under control. Man, after all, is master here. The thought will come, however—what if anything were to go wrong? What if anything were to fall or break? Everything is on to large a scale that if anything were to “happen,” the reckoning might be terrible and shocking beyond imagination. But his guide, who moves unconcerned amongst the all-pervading terrors of the place, reassures him.

“Do you have many accidents here?” he asks.

“Never,” is the reply received, “or hardly ever.”

But the old tag seems to take on a new and sterner meaning here.

And presently, as they go along, he sees a sudden blaze of light, a glory of colour, a wonder of golden fire. It is the entrance to the “Bessemer Shop.”

How is one to describe the wealth of colour first seen on the threshold of the Bessemer shop and then inside it? Here, indeed, is the subject for the brush of a great painter. Talk of colour values and tones! The dominating colour is yellow, which ranges from the faint lemon-yellow sometimes seen on the edge of sunsets fading slowly out into the night, through all shadings of primrose and saffron, [text marker: end page 292]

[text marker: start page 294] to that ruddy orange which the old ballad writers used to describe as “the red, red gold.”

Then there are all the dark hues of the machinery, “jib-cranes,” “converters,” the “ladle,” moulds and other mechanical devices, with the spectral figures of the workmen moving about, half monstrous in the broken lights. If you see the place on a bright day when the sun streams in, the light as it falls is changed into lovely violets and purples, throwing the rest of the building into strange mysterious caverns of shade.

How all this wonderland of colour is produced comes rather as a second thought. The guide first shows you the furnaces in which the pig-iron is melted down. These are called cupolas, a term which the workmen have transformed into “cupuloes.”

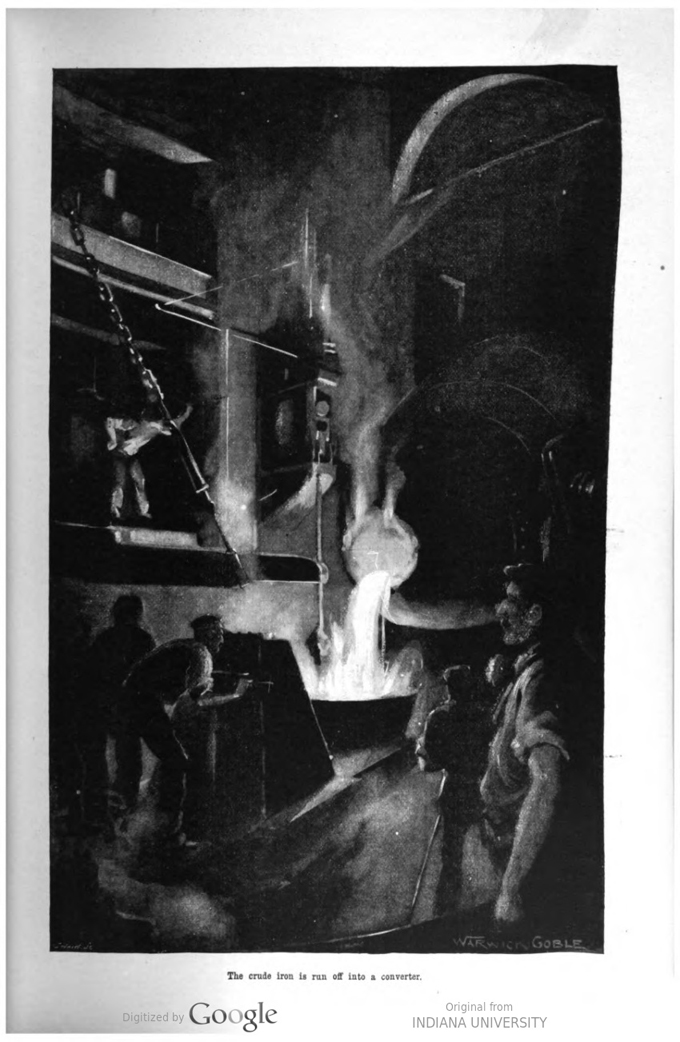

When the crude iron has been sufficiently reduced, it is run off into the converter, a large oval-shaped tank. This vessel has a curved nozzle or spout at the top for pouring the metal in and out; it is composed of massive iron plates, and lined with a fire-resisting clay called ganister. At the bottom of it is an air chamber connected by tubes with a powerful blowing engine, giving a pressure of twenty pounds to the inch of air when the full power is used.

While the pig-iron has been melting in the cupola, the converter is heated to a red glow by a fire placed inside it. When all is ready, the converter is capsized, the embers falling out amidst a shower of sparks; then the converter is placed in a horizontal position, the spout being turned to receive the glowing liquid iron from the cupola. Having received a charge of some eight tons, the converter is raised to a vertical position; there is a sudden, deafening roar, a splash and a splutter of flame and golden sparks, some of which twinkle like stars—this is the true iron, others are merely dull red bits of silica.

As the air is forced through the molten metal intense combustion ensues immediately, the first onset being marked by a shower of myriads of tiny stars and rockets, a pyrotechnic display, indescribably beautiful, far surpassing in effect any fireworks ever seen.

So far I do not think that there is much danger to the workmen in the process. I asked one of them, who was standing near me with a huge iron bar in his hand used for moving along the moulds swinging from the cranes, if many were injured by the heat and dust. There seems to be a shower of tiny atoms of dust, composed of silicious matter, constantly falling, and the men must breathe it in as they work.

He replied in a general sort of way that “very few gets hurt here.”

But the next part of the operation of making Bessemer steel looked to me decidedly dangerous.

When the air has been driven through the liquid mass of the molten iron—the colour of the flames changing into an almost ineffably pure white—and the foreman thinks that the metal is ripe for his purpose, the converter is lowered, and a workman, standing on the [text marker: end page 294]

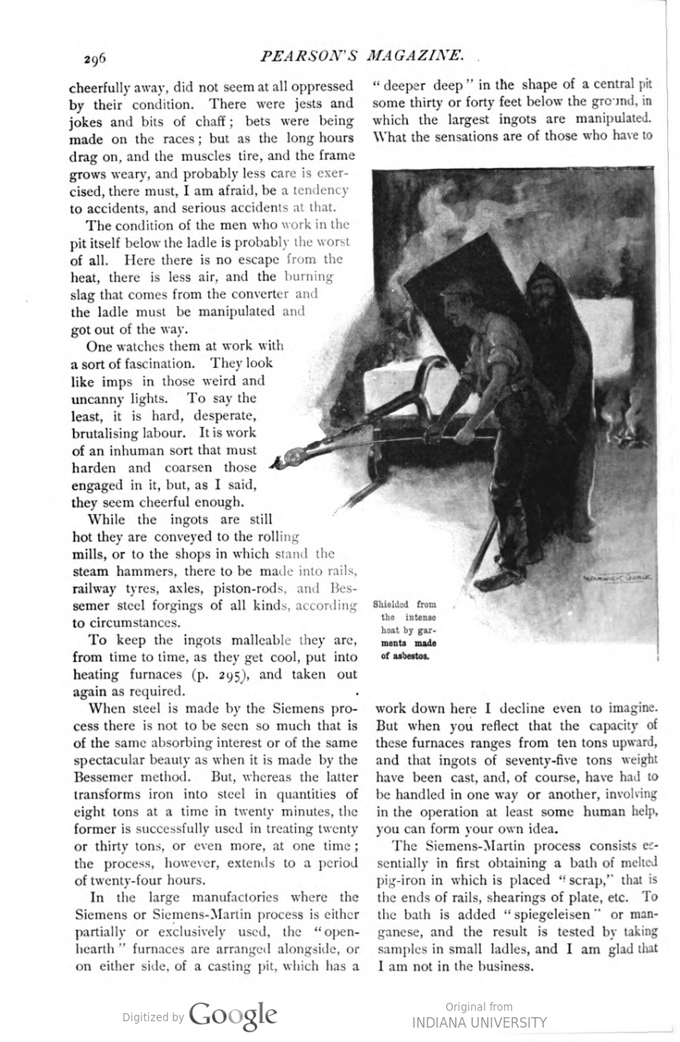

[text marker: start page 295] floor where are the cupolas, gets ready to throw in the manganese, as the iron is poured from the converter into a receiver called a “ladle,” the hue of the molten iron being at once more “beautiful and terrible” than anything I have ever seen.

The parcels of manganese are thrown into the ladle while the molten iron is being poured into it, and as the manganese strikes it long tongues of flaming metal shoot out in every direction—over the pit in which the ladle stands, over the moulds which are placed at the edge of the pit ready to receive their charge from the ladle later on, over amongst the workmen standing about.

Following this there is a sudden flash of dazzling brightness, a sharp explosion of light and flame, and this is repeated with each parcel of manganese until the requisite quantity of manganese has been thrown into the molten mass, and the steel finally made.

Then the ladle is swung round to the front of the pit, a plug is drawn out from the bottom, and the white-hot steel runs into the moulds.

The moulds are caught up by the steel teeth of the cranes, the workmen having to face the awful heat to get the teeth into position. The ingots thus formed sometimes fall out straight away of their own weight. When they stick in the moulds men have to go forward and knock them out with heavy crowbars.

The heat is intense.

In one case I saw two or three men attempt to knock an ingot out of the mould but they had to beat a retreat. However, another, who seemed of tougher material, was called upon, and with a sort of dare-devil air he advanced to the mould, and, shading his face from the heat with one hand, succeeded in hammering the ingot out with the other.

It seems scarcely possible that men who live in this atmosphere of heat and dust and dirt can be very healthy, and yet I must say that the men I saw, working sturdily and [text marker: end page 295]

[text marker: start page 296] cheerfully away, did not seem at all oppressed by their condition. There were jests and jokes and bits of chaff; bets were being made on the races; but as the long hours drag on, and the muscles tire, and the frame grows weary, and probably less care is exercised, there must, I am afraid, be a tendency to accidents, and serious accidents at that.

The condition of the men who work in the pit itself below the ladle is probably the worst of all. Here there is no escape from the heat, there is less air, and the burning slag that comes from the converter and the ladle must be manipulated and got out of the way.

One watches them at work with a sort of fascination. They look like imps in those weird and uncanny lights. To say the least, it is hard, desperate, brutalising labour. It is work of an inhuman sort that must harden and coarsen those engaged in it, but, as I said, they seem cheerful enough.

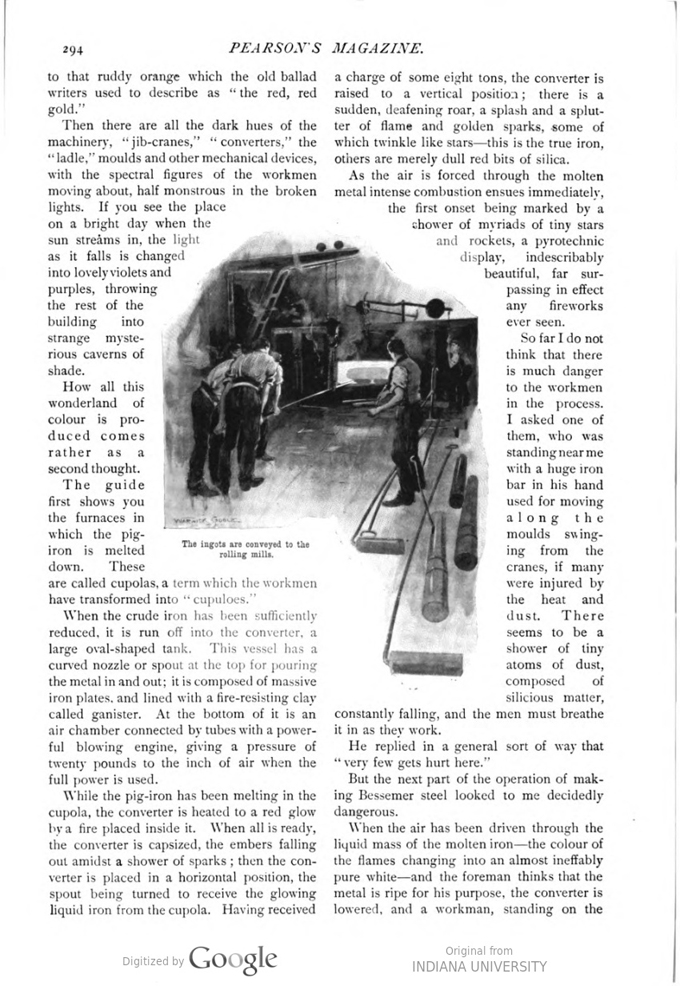

While the ingots are still hot they are conveyed to the rolling mills, or to the shops in which stand the steam hammers, there to be made into rails, railway tyres, axles, piston-rods, and Bessemer steel forgings of all kinds, according to circumstances.

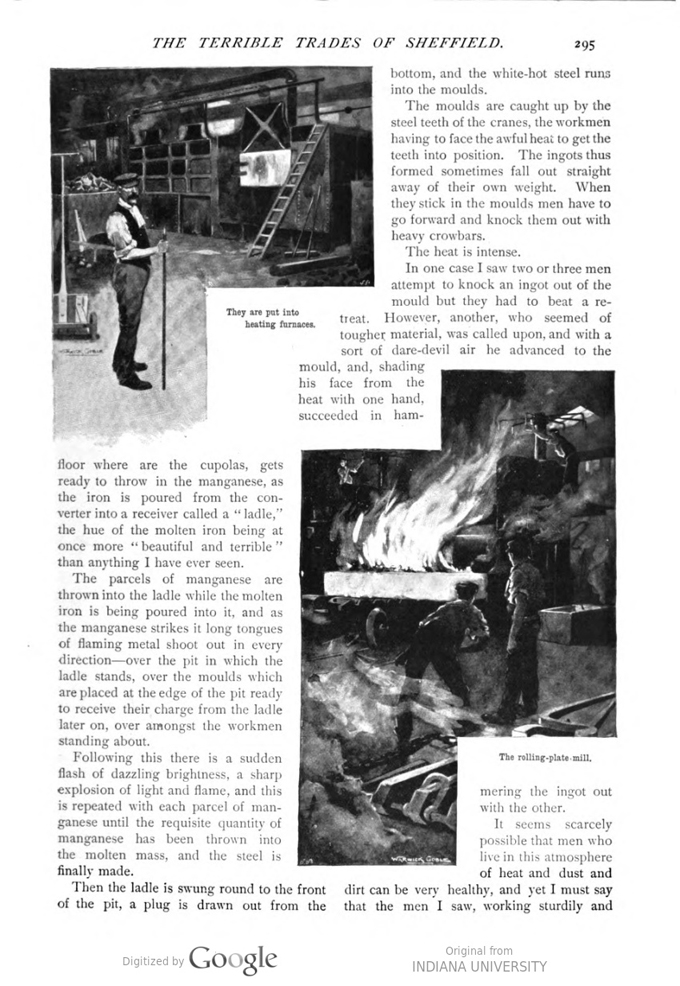

To keep the ingots malleable they are, from time to time, as they get cool, put into heating furnaces (p. 295), and taken out again as required.

When steel is made by the Siemens process there is not to be seen so much that is of the same absorbing interest or of the same spectacular beauty as when it is made by the Bessemer method. But, whereas the latter transforms iron into steel in quantities of eight tons at a time in twenty minutes, the former is successfully used in treating twenty or thirty tons, or even more, at one time; the process, however, extends to a period of twenty-four hours.

In the large manufactories where the Siemens or Siemens-Martin process is either partially or exclusively used, the “open-hearth” furnaces are arranged alongside, or on either side, of a casting pit, which has a “deeper deep” in the shape of a central pit some thirty or forty feet below the ground, in which the largest ingots are manipulated. What the sensations are of those who have to work down here I decline even to imagine. But when you reflect that the capacity of these furnaces ranges from ten tons upward, and that ingots of seventy-five tons weight have been cast, and, of course, have had to be handled in one way or another, involving in the operation at least some human help, you can form your own idea.

The Siemens-Martin process consists essentially in first obtaining a bath of melted pig-iron in which is placed “scrap,” that is the ends of rails, shearings of plate, etc. To the bath is added “spiegeleisen” or manganese, and the result is tested by taking samples in small ladles, and I am glad that I am not in the business. [text marker: end page 296]

[text marker: start page 297] However, all this must be done by somebody, I presume, and it must be allowed that danger is reduced to a minimum by the strength and excellence of the machinery that is employed, particularly in the newer and more recently constructed works.

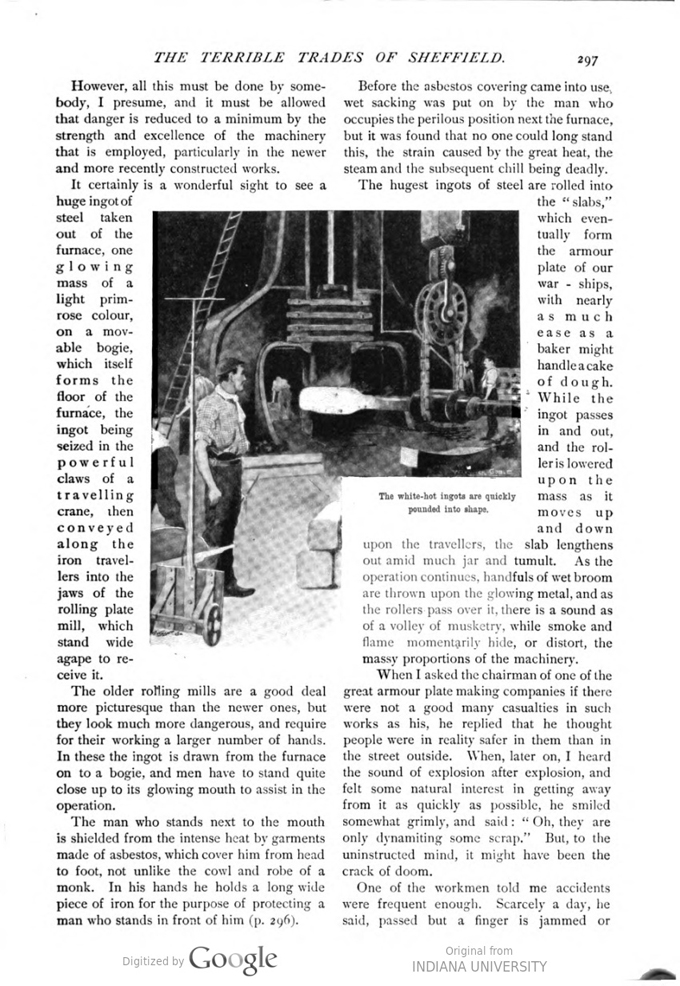

It certainly is a wonderful sight to see a huge ingot of steel taken out of the furnace, one glowing mass of a light primrose colour, on a movable bogie, which itself forms the floor of the furnace, the ingot being seized in the powerful claws of a travelling crane, then conveyed along the iron travellers into the jaws of the rolling plate mill, which stand wide agape to receive it.

The older rolling mills are a good deal more picturesque than the newer ones, but they look much more dangerous, and require for their working a larger number of hands. In these the ingot is drawn from the furnace on to a bogie, and men have to stand quite close up to its glowing mouth to assist in the operation.

The man who stands next to the mouth is shielded from the intense heat by garments made of asbestos, which cover him from head to foot, not unlike the cowl and robe of a monk. In his hands he holds a long wide piece of iron for the purpose of protecting a man who stands in front of him (p. 296).

Before the asbestos covering came into use, wet sacking was put on by the man who occupies the perilous position next the furnace, but it was found that no one could long stand this, the strain caused by the great heat, the steam and the subsequent chill being deadly.

The hugest ingots of steel are rolled into the “slabs,” which eventually form the armour plate of our war-ships, with nearly as much ease as a baker might handle a cake of dough. While the ingot passes in and out, and the roller is lowered upon the mass as it moves up and down upon the travellers, the slab lengthens out amid much jar and tumult. As the operation continues, handfuls of wet broom are thrown upon the glowing metal, and as the rollers pass over it, there is a sound as of a volley of musketry, while smoke and flame momentarily hide, or distort, the massy proportions of the machinery.

When I asked the chairman of one of the great armour plate making companies if there were not a good many casualties in such works as his, he replied that he thought people were in reality safer in them than in the street outside. When, later on, I heard the sound of explosion after explosion, and felt some natural interest in getting away from it as quickly as possible, he smiled somewhat grimly, and said: “Oh, they are only dynamiting some scrap.” But, to the uninstructed mind, it might have been the crack of doom.

One of the workmen told me accidents were frequent enough. Scarcely a day, he said, passed but a finger is jammed or [text marker: end page 297]

[text marker: start page 298] broken, or even something more serious. Fatal accidents are, however, fortunately rare.

It is hardly within the scope of this article to dwell upon any special feature of these great steel making works, but it gives one some idea of the enormous interests involved when one knows that a single armour plate often weighs twenty tons or more, and costs anywhere from £1800 up to £3000, according to size and thickness. Gigantic machines and tools of enormous strength and power are used for bending, shaping, cutting, and planing them according to the position they are to occupy on the vessel for which they are made.

The hydraulic presses and the steam hammers are interesting little things. The hydraulic press is used for forging the ingots into big marine crank shafts or other large bodies of solid steel. The presses are of different sizes in the different works.

In one large workshop, picturesquely known as the “Cathedral,” there is a forging press which exerts a pressure of 5000 tons. In another there is one of 8000 tons pressure, and, in still another, one is being constructed which will exert a gentle pressure of 10,000 tons. Very pretty toys they are, but not for children.

The same remark applies to the steam hammers, which are everywhere about. There are baby hammers and mammoth hammers, used according to the nature of the work to be done. The white-hot ingots are quickly, in a sort of grim and deathly silence, pounded into shape (p. 297), and, while their work is a triumph of mechanical ingenuity—it seems so easy and so safe—the work of the men who have to handle the ingots, put them into the furnace, and bring them back and forth to the hammer, must be fearfully hard and trying.

The only process in which the manufacture of steel does not convey to the mind an idea of terror is that where the slabs of steel are hardened in a kind of enormous shower bath. It is a beautiful sight, and forms a restful contrast to all the other operations.

Interesting as a visit is to any of the great Sheffield steel works, there is an involuntary feeling of greater cheerfulness when one gets outside into the open air.

And yet we have seen but one or two aspects of the terrible trades of Sheffield. There are many others. The making of steel wire—one of the most dangerous possible of occupations—the far-famed cutlery—knives, razors, scissors, the manufacture of saws and files and other tools and implements—all have their special perils.

[text marker: end page 298, end article]